Page last updated 29/01/04

A Tour In Westmorland by Sir Clement Jones, published 1948

CHAPTER VI

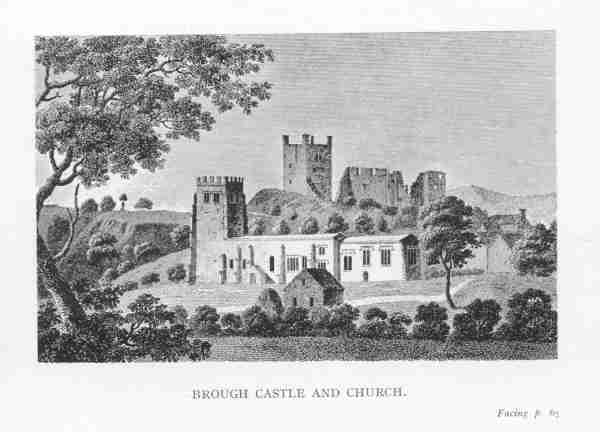

BROUGH AND RAVENSTONEDALE

The next two places on our visiting list were Brough and Ravenstonedale. Neither of them is actually situated on the banks of the Eden, but both are seated on her tributaries - Brough on the Swindale Beck and Ravenstonedale on the Scandale Beck - and both have always been important centres in the life of the barony of Westmorland. We went to Brough in the morning, to Ravenstonedale in the afternoon. They are each about four miles from Kirkby Stephen, which is, in my opinion, the best headquarters from which to explore this part of the county.

The parish of Brough is a large one; its length from north to south is about five miles; from east to west about eight. Rugged moorlands of the Pennine Chain, including what was once the greater part of the wild forest of Stainmore, occupy by far the largest portion of this area. The hilly district, which contains various minerals - lead, limestone, iron, inferior coal and barytes - has attracted commercial companies; but it is the low-lying land in the Bottom, the fertile, cultivated part and the rich meadows, to which visitors are drawn and particularly to the castle and the church.

The town of Brough, the Verterae of the Romans, was very early a place of importance, being the central station on the Maiden Way between Bowes in Yorkshire - the Roman Lavatrae - and Brougham (Brocavum). From Eboracum (York), the capital of the north, the Romans made a road, or more probably improved a native track leading in a north-westerly direction to Carlisle. At Maiden Castle, four miles east of Brough, is a Roman camp, and there is another at Rere Cross on the eastern limit of this parish beyond which, on the Yorkshire border, was a hospital for the entertainment of wayfarers crossing the dreary wastes of Stainmore. From Brough the Roman road ran by way of Kirkby Thore to Brougham, there joining the main road from the south, which had come through Westmorland via the Lune Vally and Crosy Ravensworth, and so forward to Penrith and Carlisle.

The Roman fort at Brough was built, presumably with the dual purpose of barracks and defence, on a high bluff over-looking Swindale Beck, and after the Conquest the ruins of the old fort and the strategic value of the site offered the very facilities which the incoming Norman "off-comers" wanted for their new castle.

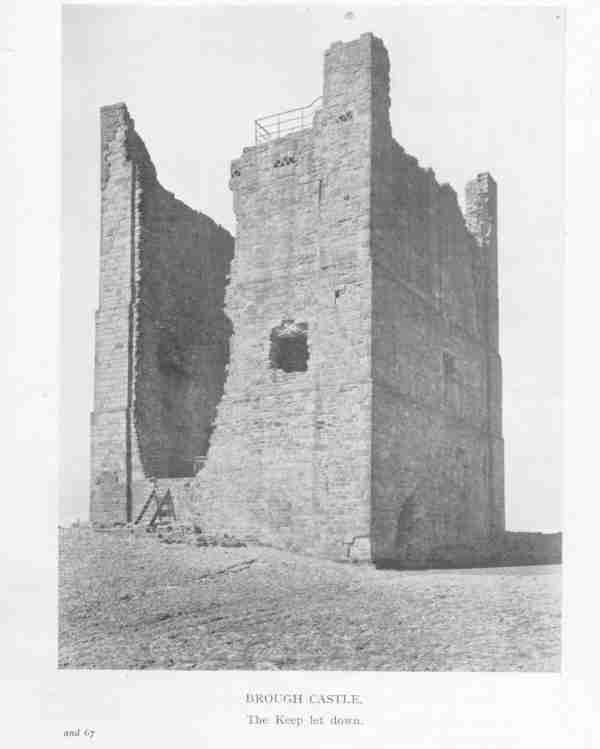

The manor of Brough after the Conquest was included in the barony of Westmorland and passed in time with that barony to the Veteriponts, Clifford and Tuftons. The castle is said to have been erected in the latter part of the Norman era, probably by Robert de Veteripont who died in 1228. The area of the castle forms what is known as a "trapezium," which means that now two sides are parallel. Its longest side - 94 yards - is next the ditch; its shortest side, which includes the keep, called Caesar's Tower, is on the west; a curtain wall, 15 feet high, enclosed the castle on the north; the keep, the principal part of the structure now remaining, consists of a basement and three storeys above; the domestic quarters, built against the south curtain, included the gatehouse, through which you go in to-day, the hall to the east of it, and beyond these, at the south-east angle, a large drum-tower, 30 feet in diameter, known as "Clifford's Tower," partially dismantled in the 17th century.

During the wars between England and Scotland the town on

several occasions was attacked by the enemy and the castle burnt. It was

repaired and was subsequently the occasional residence of the Veteriponts and

Cliffords. The castle was, however, better fitted for a tower of strength

against an enemy than for a nobleman's seat, and such it continued to be until

it was accidentally destroyed

by fire in 1521. In 1659 it was repaired by the indefatigable Anne Clifford, who

put a stone up over the gateway to record the fact that, after the restoration

of the castle, "she came to lie in it herself for a little while in September,

1661, after it had lain ruinous, without timber or any covering ever since the

year 1521, when it was burnt by a casual fire."

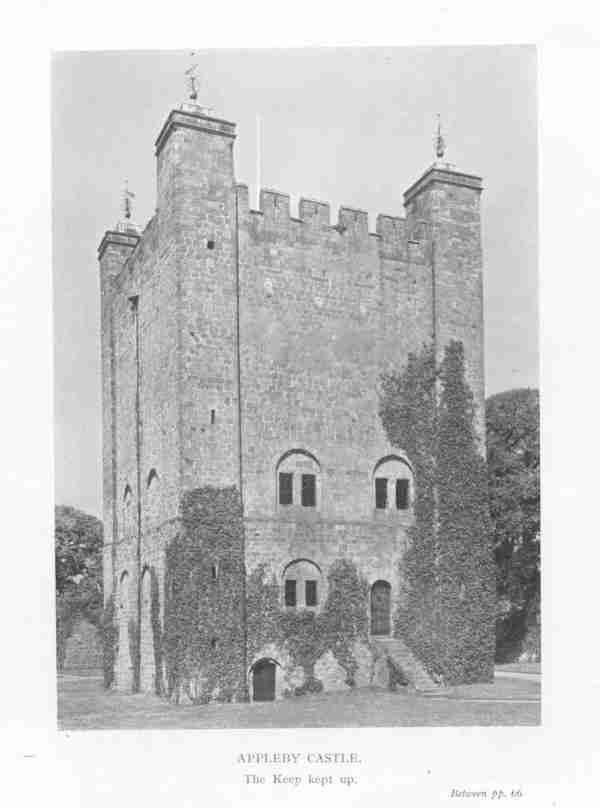

Except for the honour and glory of restoring yet one more of her castles, the Lady Anne might have saved herself the builders' bill, for in 1695 her grandson Thomas, Earl of Thanet, who had inherited the estate and was at that time carrying out extensive repairs at Appleby Castle, demolished Brough Castle and sold the timber. By 1777 Nicolson and Burn recorded that "the castle of Brough now lies totally in ruins. The whole presents to the eye a kind of venerable magnificence, the very ruins adding to the solemnity of the scene."

The ruins served as a quarry from which the inhabitants of the village obtained stone for repairing their stables and other buildings, in much the same way as the castles of Pendragon and Hartley were used. Happily for the nation what remains of the castle is now in the care of H.M. Ministry of Works, and at the time of our visit an excellent and helpful ex-serviceman was on duty as guide.

The town of Brough is like a three-decker pulpit. On the top deck is the keep and the rest of the castle; in the 'tween-deck is the church; and on the lower deck, below the church, is the vicarage. The view from the garden of the vicarage, which the vicar, Mr. Whitmore, was kind enough to show us, is unusually fine - "one of the finest in the North of England" according to one writer - including as it does, the distant Helvellyn, Skiddaw, Saddleback and many other mountains and a great part of the Vale of Eden.

The church of St. Michael is large and ancient, chiefly in the Early English and late Perpendicular styles. The south doorway is Norman (mid 12th century); it has a round arch of two moulded orders, the inner with beak-heads and the outer with chevrons. Inside the church there is much to see and many monuments of interest. There is the well-known one to Gabriel Vincent, steward to Anne Clifford, which I have mentioned elsewhere, and there is another, an elegy in memory of one Francis Thompson, for 32 years vicar of this parish, who died in 1735 aged 70 years. It contains the following lines:-

"His patron Jesus;

With no titles graced

But that best Title

A good Parish Priest."

I cannot resist quoting this, because it is so wholly true of the long ministry of my own father at Burneside, and of the devoted services of countless other clergymen in the Carlisle diocese.

In 1344 this church was appropriated by Pope Clement VI to Queen's College, Oxford. The famous Robert de Eaglesfield who was confessor to Philippa, wife of Edward III and found of that college, was at one time an absentee rector of the living of Brough. He was prosecuted by the bishop for non-residence, but pleading the necessity of attending to the care of the royal conscience, he easily obtained dispensation.1 In 1868, by a mutual exchange, the patronage passed to the Bishop of Carlisle.

In the churchyard we noticed some redstarts. This was actually the third churchyard in Westmorland in which we had seen redstarts, the other two being Martindale and Firbank. Perhaps redstarts like churchyards.

Brough Hill, which is in the parish of Warcop, has been famous

for its fair for many generations all over the North of England and is one of

the oldest fairs in the whole country. Originally it included cattle and sheep

as well as horses and lasted for two days, but now it is a one-day affair, only

for horses and "stags" (unbroken horses), and it is treated by the thousands of

people who attend it each year more for purposes of holiday than business. I

happened to be walking in the neighbourhood of Kirkby Lonsdale on the morning of

the fair last year and noticed

a long procession of cars and motor coaches filled with passengers in jovial

mood coming from Lancashire all northward bound for Brough Hill.

A farmer friend of mine told me recently that he well

remembered going to Brough fair, on business, some 40 years ago; he met a man,

while he was there, leading two foals on a halter, about two and a half years

old each, ready for breaking-in, and the man was very pleased because he had got

£50 each for them. "To-day," said my friend, "the man would get at least twice

that sum." I should have been more impressed by these figures and the rising

price of young horses, had I not read that morning in the Times that, in another

branch of transport, the cost of a modern passenger liner is not far short of

two and a half times what it was before the war.

A farmer friend of mine told me recently that he well

remembered going to Brough fair, on business, some 40 years ago; he met a man,

while he was there, leading two foals on a halter, about two and a half years

old each, ready for breaking-in, and the man was very pleased because he had got

£50 each for them. "To-day," said my friend, "the man would get at least twice

that sum." I should have been more impressed by these figures and the rising

price of young horses, had I not read that morning in the Times that, in another

branch of transport, the cost of a modern passenger liner is not far short of

two and a half times what it was before the war.

WINTON

On our return journey from Brough we stopped at Winton, a small village with some pleasant domestic architecture, one mile north of Kirkby Stephen. It has no church and not many houses, but it had a school in the 18th century which helped to produce two well-known scholars - the Rev. John Langhorne, D.D. (1835-1779), and Richard Burn, LL.D. (1709-1785). Both of these worthies of Winton started their education in this village where they were born. Langhorne went on afterwards to Appleby Grammar School and Clare, Cambridge, and became a prolific writer both in prose and verse. In conjunction with his brother William he translated Plutarch's "Lives." He became rector of Blagdon in Somersetshire, and towards the end of this life a prebendary of Wells Cathedral.

Richard Burn was the son of a substantial yeoman or 'statesmen; at the age of 20 he went to Queen's College, Oxford, and was afterwards ordained and appointed vicar of Orton. But perhaps he is best known for his collaboration with Joseph Nicolson in compiling "The History and Antiquities of the Counties of Westmorland and Cumberland," a work which still maintains its place as the best of all our county histories. No-one knows better than I do, after constant reference to it, what a mass of information it contains, how freely I have borrowed from it, how grateful I am to the writers of it; my only regret is that it is so hard to get a copy of it. It is this fact that makes me "crib" whole chunks from it, in the hope that they may be of interest to those who have not themselves got access to the two large volumes of Nicolson & Burn. In the volume on Westmorland, after dealing at some length with Dr. Langhorne's works and connection with Winton, all the Dr. Burn has to say about himself is written with charming modesty in exactly one line: "This village also the compiler of these memoirs boasts as the place of his nativity."

RAVENSTONEDALE

There are place-names in Wales of such length that few Englishmen can even attempt to pronounce them, and by comparison Ravenstonedale seems a short, snappy little name. Nevertheless, it has proved too long for general use in Westmorland and has been shorted into "Rissendale" for ordinary talking purposes.

The parish of Ravenstonedale is very extensive - not as large as Brough but about the same acreage as Dufton, and, like both of those parishes it provides a great variety of scenery, from the huge mountain heights down to the lovely valleys below, on one of which is the village itself. The whole parish is included in one township but it is divided into four "angles" or parts, namely, the Town Angle, Bowderdale Angle, Fell End Angle and Newbiggin Angle.

The ancient Briton, who were here, have left behind them but few traces of their occupations, but in the Fell End Angle, the south-eastern quarter of the parish near Rawthey Bridge, there are megalithic remains of a stone circle.

The manor of Ravenstonedale was granted to the Gilbertine canons of Watton (Yorkshire) probably late in the 12th century. To them also belonged the rectory of the church. The ruins and foundations of their establishment or cell are in the churchyard immediately north of the existing church and were excavated in 1927-8. This order was founded by St. Gilbert in 1148 and enjoyed many privileges, in all of which Ravenstonedale participated; for instance, they were exempted from payment of tithes for land which they themselves cultivated, and these rights were confirmed by King John, Henry III, Edward III and Henry VI. The monks also enjoyed the privilege of sanctuary; if any person guilty of a crime punishable by death escaped into Ravenstonedale and succeeded in tolling the holy bell in the church tower, he was free from arrest. This privilege was abolished here as elsewhere in the reign of James I.

After the suppression of the monasteries, Henry VIII granted the manor and church of Ravenstonedale first to the Archbishop of York, during the lifetime of that prelate, and a few years later to Sir Thomas Wharton, whom he created a baron. Philip, Lord Wharton, began the formation of Ravenstonedale Park, on either side of the Scandale Beck on the north border of the parish, which was enclosed as a deer park in 1660. It was surrounded by a stone wall still in part standing to a height of nine feet. The area enclosed was about 520 acres. Much of the walling was done by "love-boons," that is voluntary labour of the inhabitants of neighbouring townships who went to get and lead (i.e. cart) stone for the work. A number of tenants were removed from their holdings when the park was enclosed, and they received in exchange allotments in other parts of the manor.

The church, dedicated to St. Oswald, was built in 1744, close to the site of the old edifice. Two of the most noticeable features inside the church are the "three-decker" oak pulpit, standing on the north side of the nave, which contains a seat for the parson's wife on the top tier; and the arrangement of the seats, all of dark oak, which face each other giving the effect of a college chapel. Mediaeval materials from the old building have bee worked into the chancel arch and the north porch, while the south porch entrance is of the 13th century re-set, but the church is in the main a good and complete example of the early Georgian period.

Apart from the established church, Nonconformity flourished here under the influence of Philip, 4th Lord Wharton, who was a Presbyterian and a colonel in Cromwell's army. With his aid a Presbyterian chapel was built which is still standing, though it changed in 1811 from the Presyterian to the Congregational sect.

No record of Ravenstonedale would be complete without mention of the Fothergill family, whose name still lingers in the dale. Fothergills have been resident here for four centuries, and many of them have risen to distinction. In the reign of Henry VIII, Sir William Fothergill was standard bearer to his neighbour Sit Thomas Wharton at the battle of Sollum Moss. George Fothergill of Tarn House, who died in 1681, was Clerk of the Peace for Westmorland. Thomas Fothergill of Brownber, who founded the endowed school at Ravenstonedale about the year 1688, was master of St. John's College, Cambridge; George Fothergill, D.D., was principal of St. Edmund's Hall, Oxford, 1751-60; Thomas, his brother, was provost of Queen's College, Oxford, 1767-96, and was vice-chancellor of Oxford University; Anthony Fothergill of Brownber was the author of several tracts; another Anthony Fothergill was a well-known doctor who, after studying in Edinburgh, Leyden and Paris, practised in London and Bath and died in 1813. No mean list for one family. The Fothergills were large landowners and had three separate estates in the parish - Tarn House, Brownber and Lockholme.

Ravenstonedale is a good centre for walking, and the walk we took was along the Scandale Beck. There we saw, amongst other birds, grey wagtails and an amusing family of dippers which we watched for a while. They appeared to be a complete family - three young ones and the parents. They all seemed to be making a great fuss about something, some family pow-pow perhaps, and then they separated; papa flew away upstream to the south as if in a great hurry to get back to the office or the golf links, whilst mama went off with the children for a picnic in the opposite direction.

On our way back to Kirkby Stephen we visited Tarn House, the early home of the Fothergills which has been described in several books on old houses.2 In the reign of Charles II it was the only slated house in the parish. It was built in 1664 by George Fothergill, who was Clerk of the Peace, and Julia his wife, and their initials and date are cut in a panel on the porch to the front door and over one of the doors of the outbuildings across the yard. The south front retains its original stone-mullioned windows.

Tarn House is a lonely farm in an exposed position on high ground. Without being told, one could guess what the force of the blizzard of 1947 must have been like, day after day, up here, but we were given grim details of how the stocks of food, stored up with such care and economy, had almost run out; even the bacon - that pendulous provender of the ceiling - which was being kept for the coming clippings and other special occasions, had to be eaten.

1 Pennant's "Tour," 1773.

2 In "Historic Farmhouse," p. 114. Westmorland Gazette Ltd., 1944; and in "Historical Monuments Survey," p. 198, H.M. Stationery Office, 1936.

Thanks to Diane Coppard in Leicestershire for transcribing this! Reproduced by permission of Tim Clement-Jones.