The location of Byrkeknott

A 15th-CENTURY IRON

SMELTING SITE

R. F. Tylecote

Manuscript received 12 August 1959.

The

author is at the

Department of Metallurgy, University of Durham.

SYNOPSIS

The account roll relating to the early 15th century smelting site known as Byrkeknott, in Weardale, Co. Durham, is one of the most informative documents dealing with the direct process. An attempt has been made to locate this site. An iron smelting site, answering to the description given in the roll, has been excavated and some metallurgical remains, which are datable to the 14th-15th centuries, have been found. There is a strong possibility that the site excavated is that of Byrkeknott, and on this basis an estimate of the yield has been made.

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

IN THE OLD CHRONICLES and records of the See and Palatinate of Durham there are frequent references to the iron mines of Weardale, and the sale of iron afforded the bishops a fruitful source of revenue. The usual practice was for these mines to be farmed out together with the forests which supplied the charcoal. Bishop Langley, however, 'tried the experiment to work his own iron', and a suitable site beside a stream, was chosen to build a bloomery.1

Many of Durham's records were destroyed in the 17th century and it is fortunate that an account roll2 of Bishop Langley was preserved. This is one of the earliest surviving documents giving useful information about iron smelting. Lapsley, an American engaged in writing a history of the Palatinate of Durham, found it in the course of his research and transcribed it in 1899 under the title: 'The account roll of a fifteenth-century iron master'.1 A detailed description is given of a newly erected bloomery at Byrkeknott, near Bedbourn in Weardale, Co. Durham, and of operations carried out in one year from November 1408-9. Only one earlier comprehensive account of a bloomery has been preserved, that for Tudeley near Tonbridgo in Kent; the accounts cover two periods; from 1329-34, and from 1350-4.3

The Langley account

roll states that the bloomery was

erected at 'Byrkeknott juxta Bedbourne'

and that

Bedbourn was in early times divided into South and North

Bedbourn. In Hatfield's Survey of 1345–874 South Bedbourn covered an area west of

the Wear and north and south of Bedbourn River. North

Bedbourn covered an area east of the Wear and the village

itself was situated between Greenhead and Firtree. The

survey gives the names of tenants holding land in the two

parishes, and a few of these names occur in the account roll

in connexion with the bloomery.

Today only the parish of South Bedburn remains. Bedburn village consists of a few houses, a hall, and a mill. The mill was known as 'Bedburn Forge' early in the last century and Lapsley drew the conclusion that 'Bedburn Forge' was the old Byrkeknott. The history of the mill goes back a very long time, but it does not seem to have been used for metallurgical purposes, except in the 19th century. It is first mentioned in 1314 as being a fuller's mill,5 and in 1551 there is a reference to a fulling mill at 'Hoppylandknottcs'.6 Early in the 18th century Bedburn Mill might have been used as a cornmill since a miller is recorded as having died there in 1741.7

The records also show that a blacksmith lived at 'Bedburn Mill' in 1799. The mill itself was a bleachery in 1820, when it came into the possession of William Dodds, a manufacturer of edge-tools and shovels.8 Later, in about 1860, it was used as a sawmill.9 There is a mill-race about half a mile long, but no stream joining the river Bedburn up-stream of the mill which could be identified with 'Heribourne'.

A survey of the area

showed that barely half a-mile to the east is a ruined mill

known as Harthope Mill, near a small stream called Harthope

Burn. Harthope Mill fits the description of Byrkeknott much

better than Bedburn Mill. The millrace is only 100 yd long

and we know that one mason and four labourers were employed

to construct it and to line part of it with stone at a cost

of 50s 4d in 30 days.1 It seems unlikely that this could

have been done with the much longer millrace at Bedburn

Mill. Moreover Harthope Burn might have been the

'Heribourne' from which the watergate (millrace) extended.

As late as 1828 this burn

was known as the Harehope Burn, and the mill as Hartup Mill,

in the same document.'°

To the west of Harthope

Mill are the `Knotty Hills', overgrown with birch trees.

Byrkeknott might possibly have derived its name from these

hills, but the fact that the only mention of this name seems

to have been in the account roll of Bishop Langley, leads

the author to draw the conclusion that the name was given by

the bishop to the new bloomery.

North of the Knotty Hills is Hoppyland whence cinders were taken to the bloomery. Hoppyland Hall was at that time rented out to Sir Radulphus Eure,4 who supplied the bloomery with iron ore from his mines in 'Rayley', 'Hertkeld', and 'Morepytt', near Evenwood, three miles south-east of Bedburn. In 1433 these same mines were farmed out to William Eure at an annual rent of £112 13s 4d.

11

The building of the

bloomery went on under the personal supervision of John

Dalton, ironmaster. The equipment and tools were either made

on the spot or bought individually as required. The building

was made of timber and roofed with turf. The bloomer made

the bloomhearth and the stringhearth and was assisted by

another bloomer from a neighbouring bloomery. A carpenter

made the waterwheel, gates (sluices), wooden spouts

(launders), the bellows, and other necessary wooden

instruments.

Among the tools assembled were axes, hammers, rakes, three

long iron rods, (all made by a smith in West Auckland), two

measures for the ore, scales for weighing the iron, and a

sieve for sifting the ore. The ore was brought from mines in

Weardale and twelve cartloads of cinders came from a field

at Hoppyland.

The

carpenter built four huts in four days, and the wood and

charcoal were supplied from Bedburn Park. The bloomer as

well as the foreman lived on the spot, and their wives

helped in breaking and sifting the ore and on occasion

worked the bellows.

In

the week beginning 17 November 1408, work started and the

bloomer tried to smelt the ore. No blooms were produced for

the first two weeks, but in the third week the bloomer

produced six blooms. From then on about six blooms of iron

were produced every week, each bloom weighing 195 lb.

A

duodena was the measure for charcoal, and about

In

the first few weeks a few adjustments had to be

Wooden trays were used to carry the ore and these were

probably made on the spot while a carpenter was available;

later they were bought outside.

The

quantity of iron produced is given in the roll; this and the

calculated charcoal rate, percentage yield of iron, and

quantity of slag produced during the year are given in Table

I.

Total slag produced (assuming charcoal contains 3 % ash)

TABLE I Annual Input and output

Total ore supplied

341 tons

Total iron produced

24.3 tons

Average output of iron

1200 lb/week

Actual

yield of iron (lb Fe/lb Fe in ore)*

16.5%

Charcoal rate for two hearths

12.9 tons/week

Assume

½

for smelting; charcoal rate per lb of Fe

12 lb

326 tons

*

Based on analysis of nodule given in Table II, col. C

EXCAVATIONS AT HARTHOPE MILL

The site

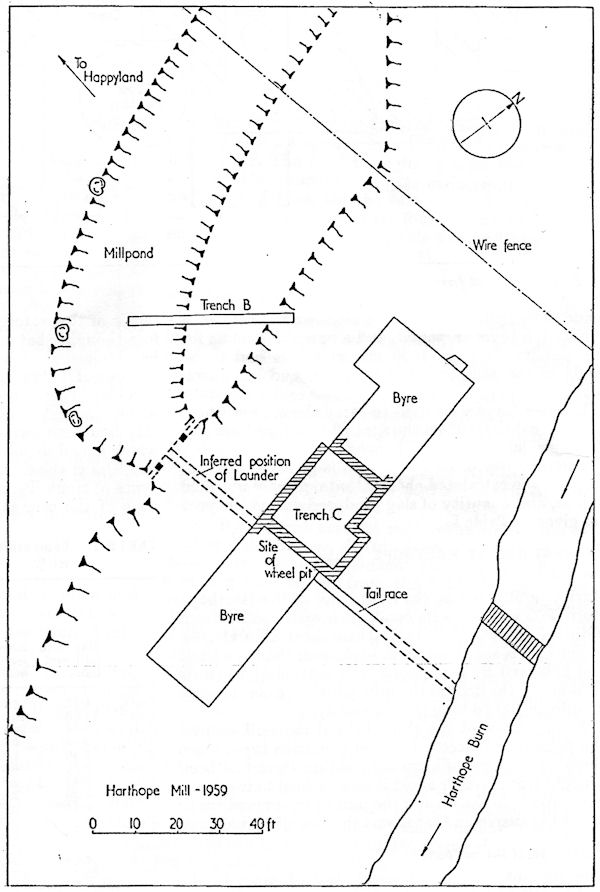

Harthope Mill lies on the right bank of the Harthope Burn,

200 yd before its confluence with the Bedburn (Gridref.

NZ108322-25 in. Durham sheet XXXIII.10).

The

mill is set about 40 ft back from the burn itself and is

served by a millpond, the bottom of which is 15 ft above the

floor of the mill, which in turn is fed by a millrace 100 yd

long (Figs.1 and 2).

Examination of the slope behind the mill showed the presence

of pieces of slag of primitive type. Since there was no way

of knowing whether these had been brought from further

afield it was decided to carry out excavations in the area

of the mill to try to confirm or reject the suspicion that

it was the site of Byrkeknott.

Excavation of the millpond

The

account roll gives a great deal of space to the

repair of the watergate or millrace, and it was therefore

thought that some useful dating evidence might be obtained

from a trench cut through the millpond and one of its banks

(trench B, Fig.2).

A

clay layer formed the bottom of the pond and ran under the

east bank for a considerable distance. The clay had been

formed naturally because the shelf, on which it had

deposited had been part of the old river bed. Under the clay

are water-worn pebbles of various types of stone. Presumably

the bank was built on the edge of the clay layer to prevent

seepage, and well

No dating evidence was

found in the bank or the pond, but a considerable number of

pieces of primitive slag were found in the bank and the

up-cast to the east of it. The composition of this slag is

given in Table II, col. A. It would appear that the bank

itself was constructed by the tipping of material gathered

from the surrounding area after iron smelting operations had

been carried out. Since the composition of the slag it

contained is no guide to dating, the production of this slag

could be synchronous with a Byrkeknott (1408) phase of the

site, or related to a possible earlier phase such as that at

High Bishopley (12th–13th century).12 Some potsherds

belonging to the earlier period were found in a field 200 yd

to the south-west of the site, in conjunction with

iron-bearing cinder of primitive type (see Fig.1).

The eastern section of the bank, which does not bottom onto clay, consists of sandy material containing slag which is almost certainly material excavated from the actual site of the mill when it was cleared or enlarged.

| TABLE II Composition of material from Harthope Mill, wt-% |

||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| Slag from millpond bank | Slag from ferruginous layer | Partly roasted ore nodule | Compacted fines from roasting (yellow) | Red fines from ferruginous layer | Unroasted nodule according to Tomkieff13 | |

| Fe203 | 4.98 | 2.82 | 62.48 | 34.59 | 31.6 | 6.71 |

| FeO | 38.96 | 40.97 | 9.18 | 1.24 | nil | 44.05 |

| SiO2 | 29.44 | 32.40 | 7.60 | 48.70 | 8.62 |

|

| Al203 | 9.68 | 6.90 | 4.72 | 2.28 | 2.89 |

|

| TiO2 | 0.40 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.20 |

|

| MnO | 2.44 | 6.73 | 0.88 | 0.08 |

... | |

| CaO | 5.46 | 2.80 | 0.84 | 2.17 | 0.94 |

|

| MgO | 4.90 | 2.70 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.77 |

|

| S | 0.14 | 0.034 | 0.032 | 0.021 |

... | |

| P205 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.22 | 0.25 |

... | |

| CO2 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 6.70 | 1.94 | 28.35 | |

| Combined H2O | 1.20 | 1.00 | 5.60 | 6.02 | 4.23 |

|

| Total |

98.29 |

97.18 | 99.10 | 98.33 | 96.76 |

|

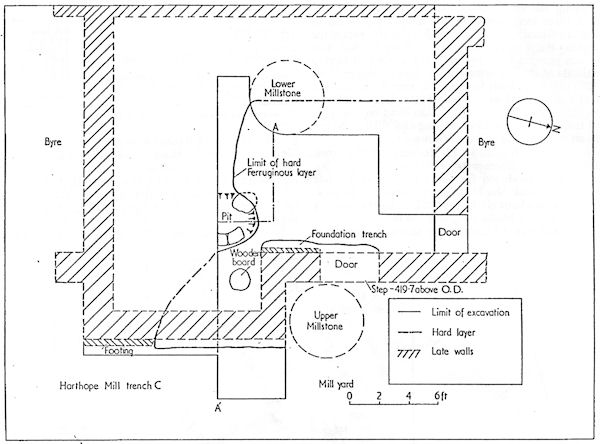

Excavation of the mill

The central section of

the mill is now roofless and derelict, but the miller's

house on the north side and buildings on the south side have

been converted into byres.

The section excavated had

housed the milling machinery, and the bottom millstone

appeared to be in situ surrounded by the remains of a

flagged floor. This floor was removed exposing a layer which

was obviously-18th–19th-century fill. It consisted of black

earth containing coal, numerous potsherds, pieces of iron, a

1-lb lead weight, a cast-iron weight, and a few iron

candlesticks. It appeared that this material had been put

down to level the floor before placing the flags in its last

phase.

3 Plan of nill and ferruginous

layer

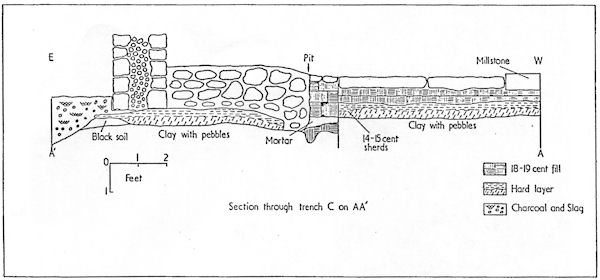

Under this layer was a

hard, highly ferruginous layer varying from 2 to 7 in.

thick; below was natural clay, now stained or burned red,

with a pebbly subsoil

beneath. This ferruginous layer covered an area roughly 17

ft x 15 ft (Fig.3) but originally it may have been

larger. The hard ferruginous layer contained a considerable

amount of slag, charcoal, iron-ore nodules, and fines. On

the east side it had been cut through in some places by the

foundation trench of the mill-wall; but some parts of this

wall had been built direct on to the hard layer (Fig.4).

4 Section through ferruginous

layer

Metallurgical finds

The slag was of a

somewhat different kind physically from that found on

primitive smelting sites of Roman or early medieval date.

The porosity was much finer and more widespread, giving it a

honeycomb texture. The upper surface was smooth and typical

of a tapped slag. As seen from the composition given in

Table II, col. B, this slag has a slightly higher silica

content than the slag found in the bank, and it suggests a

higher temperature and a more powerful blast; but it is

still a high iron-containing slag typical of the primitive

or direct smelting process.

The

Byrkeknott account roll2 refers to the use of

`sindres a dicto campo de

Hopyland . . . pro ferro novo ibidem cum ejusdem

temperando'. The suggestion here is that slag was carried

from the field of Hoppyland nearby to modify the iron

produced in the new bloomery. The slag or cinders used could

have been those produced by earlier ironworkers in the area,

as suggested, but their purpose is not certain. One

possibility is suggested by the respective analyses of slag

{Table II, col. B} and ore {col. C}. The ore is

comparatively low in silica and manganese oxide content,

while the slag from the same ferruginous layer is high in

both. Even allowing for such a high yield of iron as 20%, it

is difficult to see why the manganese content of the slag

should be so high, unless additional material high in

manganese has been added. As shown in an earlier paper12 the

manganese oxide content of the local bog ores can be as high

as 15.5% giving slags containing 13% of manganese oxide.

If

an appreciable amount of such slag was charged with the ore

shown in Table II, col. C, a slag containing

the percentage of

manganese oxide in col. B could result. The main function of

the fayalite-type slags found in this process is to remove

the gangue at a normal working temperature of about 1200°C.

The lime content of the ore is low and added lime would not

be dissolved by the slag at such a low temperature. Thus the

only way of reducing the amount of iron lost in the slag

would be to add slag relatively low in silica, which would

act as a flux and absorb some additional silica if the

working conditions were correct. It is suggested that by

working at temperatures somewhat higher than the minimum of

1150°C, and using strongly reducing conditions, the earlier

low-silica slags could have their silica contents increased

from 20 to 30%.

A microexamination of a

piece of slag from the ferruginous layer showed it to

consist of laths or plates of fayalite in a glassy matrix

(probably a melt of tridymite and fayalite). There 'were

also some small particles of metallic iron and some

magnetite dendrites. The smaller holes seemed to be filled

with a dark phase which was probably hematite or limonite.

Various forms of iron-oxide-containing material were found.

The most important was argillaceous nodular iron ore which

probably came from bell-pits in the Evenwood area to the

south of the site, which is the area mentioned in the

account roll. Some of the nodules had been roasted, others

were as mined (see Table II col. C for

composition).

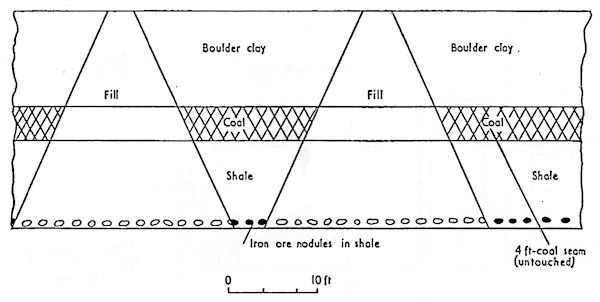

At the time of this excavation (April 1959), an open-east coal excavation was being carried out at Rowntree Farm, near Evenwood (grid ref. NZ118285), which exposed some bell-pits. It is clear that those had been worked for iron, as the workings had gone right through the coal to the nodular ore beds below, and no attempt had been made to remove more than the necessary coal to allow access to the ore beds. Part of one of these pits is shown in Fig.5 and their disposition is shown diagrammatically in Fig.6. They are of typical medieval type. The formation and occurrence of nodular ores in the coal measures has been discussed by Tomkieff.13

5 View of filled bell-pit going

through coal, exposed by open-cast working

(scale: hammer = 1 foot long)

6 Section through bell-pits

showing depth of coal and nodular ore in shale

Some of the ferruginous

material found in the hard layer consisted of fines of lower

iron content than the nodules (Table II). This material

probably came from the surface of the nodules after

roasting; the surface layer, according to Tomkieff, being

rather poorer in iron than the interior. A lump of hard

sandy material was also found, which at first sight looked

natural. It contained, however, small pieces of coal (¼-in.

cubes) and some wood, and appears to have been low grade ore

or fines compacted during roasting (see Table II, col. D for

composition).

Some doubts are often

expressed as to the impossibility of using coal in the

direct process, since although the pickup of sulphur from

coke in the modern blast furnace process is relatively high,

in the direct process with lower temperatures and iron in

the solid state, the pickup of sulphur might be expected to

be much lower. Also coal coke is often used for fuel in the

smithing hearth. For this reason it is worth mentioning

that in tests carried out in this department on pure iron in

contact with molten iron sulphide at 1000°C for 24 h, the

pickup was found to be high enough to produce continuous

intergranular films of iron sulphide which could destroy

the properties of the metal. With porous reduced ore at

1250°C, pickup of sulphur would be expected to be easier and

the use of coal for the smelting process, as opposed to the

roasting process, is out of the question. It would not be

expected that the presence of

sulphur under the oxidizing conditions of roasting would be

deleterious, nor of course is it deleterious in smithing

when the metal is in the massive state for only a short time

in relatively oxidizing conditions. Further work on this

aspect of primitive smelting is obviously required.

It is debatable whether

the shortage of charcoal was the cause of the final demise

of the site as an iron smelting works. Perhaps towards the

end unsuccessful experiments were made on the use of coal

instead of charcoal.

Charcoal

Charcoal from the ferruginous layer was made from a wide range of trees. Seventy-four per cent was made from birch wood, 14% from poplar or willow, 8% from hazel, and 4% from maple. No charcoal was made from beech wood and oak was also entirely absent, which is in marked contrast to High Bishopley where 90% of the charcoal was from oak wood.

12

Pottery

The only potsherds found

on this site that were well stratified were in the hard

ferruginous layer and consisted of a reddish-grey ware with

a green glaze on the outside, which were dated as 14th–15th

century. One piece was a rim, which suggested a flagon-type

vessel with a rim of about 5 in. dia. A roughly circular

piece of birch wood, 12 in. dia., 3/4 in. thick with the

grain running in the direction of the diameter was found

embedded in the upper surface of the hard layer, and might

have been a platter.

Hearths

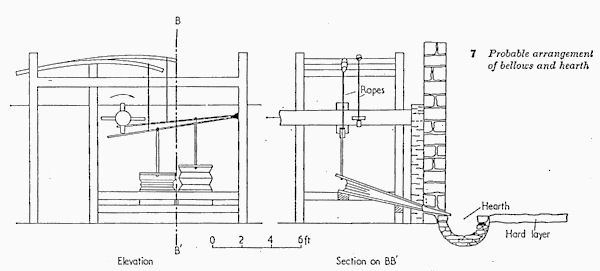

Unfortunately no direct evidence of a hearth was found. It would be expected that at this time the smelting hearths would be of the Catalan typo sunk into the ground as shown in Fig.7. They could have been raised on stone platforms as shown by Agricola as being in use in Germany about 1550.

14

The only suggestion of a

hearth was the dip in the hard floor on the south side

(Fig.3) which contained stones on which the hard layer had

been deposited. As the remains of a hearth at this point

would probably have made levelling difficult in the

reconstruction of the 18th century they might have been

removed together with any residual cinder.

The hearth would have to be large enough to produce blooms weighing about 200 lb, the order of size normal for the 15th century and mentioned in the account roll relating to Byrkeknott. Agricola's hearths were only 18 in. dia. and were capable of producing blooms weighing 2–3 cwt from a rich ore.14 Percy gives much the same dimensions for the square Catalan hearth in use for similar sized blooms in the 18th century. 15

The roll mentions the

existence of two hearths, the bloomhearth and the

stringhearth. It would seem to be impossible for the area

excavated to contain more than one hearth. It seems more

probable that the other hearth was to the south of the

wheelpit (see Fig.2) giving a more or less symmetrical

arrangement. The absence of hammer scale in the area

excavated strongly suggests that it contained the

bloomhearth, and not the stringhearth where scale would be

expected. Hammer scale (Fe3O4) has recently been found by

the author in a Roman site in Norfolk and appears to be

capable of remaining unchanged for over 1600 years.

Bellows

The roll refers to the

use of a rope and a swordblade in conjunction with the

bellows. The position of the working floor in relation to

the wheel-pit, the height of the shaft above floor level,

and the probable position of the hearth, suggest an

arrangement as shown in Fig.7, where the bellows are in line

with the axletree and driven by cams by means of a lever

system using ropes and push rods, together with saplings as

return springs.

Individual details of the

mechanism would be well known to the people of the time, and

the method would permit hand working if the water supply

proved insufficient.

CONCLUSIONS

The following

considerations provide sufficient circumstantial evidence

to associate this site with the Byrkeknott of the account

roll:

1: It is close to

Hoppyland and takes its water from the Harthope Burn which

can be equated with 'Heribourne'. It lies a short way back

from the burn in a position which is almost unique on that

river. The millrace is a reasonable length (only 100 yd)

unlike that of Bedburn Mill which is ½-mile long and which would appear to be a

much more difficult undertaking for a comparatively early

period. In spite of this Harthope Mill provided a head of 15 ft,

and therefore would be an obvious first choice, if available,

for conversion. It is still 'juxta Bedbourne', being only 200

yd from that river.

2.

It contains a hard

ferruginous working floor consisting of the elements of

primitive iron smelting, i.e. charcoal, ore, and slag.

3.

The floor contains well

stratified pottery belonging to the 14th–15th centuries.

The ore

used at Harthope Mill was an argillaceous carbonate ore in

nodular form, probably from the neighbouring coal measures. The

charcoal was mostly birch, and the slag was a typical primitive

type consisting mainly of fayalite.

The head

of water available was 15 ft, and for most of the year the

quantity should have been sufficient to

keep two hearths going continuously.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks

are due to the owner, Capt. N. P. Parlour, and the tenant, Mr J.

Wallis, for permission to excavate; to Elizabeth Tylecote for

the historical research, to Mr J.

Newick and Mr E. J. Wynne who did a considerable amount of the

excavation, and to Stewarts and Lloyds, Ltd, who did most

of the analyses.

REFERENCES

1.

G. T.

LAPSLEY: English Historical Review, 1899, 14, 509.

2.

BISHOP LANGLEY: 'Durham

Chancery Roll', Ann 27.m.7, (P.R.O. Durham Cursitor 37).

3.

M. S. GUISEPPI: Archaeologia,

1913, 64, 154.

4.

BISHOP HATFIELD'S SURVEY, 1857, .Surtees Soc., Durham.

5.

Registrum Palatinum

Dunelmense, 2, 1248, 1873-78, London.

6.

Proc. Soc.

Antiquaries, Newcastle, 1921, 9, (3rd series), 276.

7.

Hamsterley

Parish Register.

8.

W. WHITE and W. PARSON:

'Directory of Northumberland and Durham', 234; 1828.

9.

C. SURTEES:

Durham Parishes, 1925, 2, 26.

10.

E. WOOLER:

Proc. Soc. Antiquaries, Newcastle, 1905, 1, (3rd series), 64.

11.

G. T. LAPSLEY: 'The County

Palatine of Durham'; 1900, London, Longmans.

12.

R. F.

TYLECOTE: JISI, 1959, 192, 26-34.

13.

S. TOMKIEFF: Proc. Geologists' Association, 1927,

38, 618.

14. G. AGRICOLA: 'De re metallica': translated from the first

15.

J. PERCY:

Metallurgy, 280; 1864, London.