A Tour In Westmorland by Sir Clement Jones, published 1948

CHAPTER VIII

HIGH CUP NICK

HIGH FORCE - CALDRON SNOUT - CROOKBURN BECK

When the weather is mentioned in the headlines of newspapers

instead of being tucked away, as it normally is, in small print at the bottom of

the page, or, in still smaller type, along with lighting-up time at the top, you

may be sure that it has not escaped the notice of hikers and holidaymakers in

their home-going postcards. On 2nd June, when we started our tour, the heat was

very much in the news as well as on the road. "Hottest weather for 92 years" we

read; on the 4th the story was much the same: "Six days running over 85." But

there were some sinister looking clouds while we were at Kirkby Stephen and we

assured each other that we had better make the best of the fine weather. It

wouldn't last. And, for once, we were right; during the next two days there was

a drop of 28 degrees, and by the time we reached Middleton-in-Teesdale on the

6th it was even colder and wetter than when we left Kirkby Stephen.

Our plan in coming to Teesdale was to see the Pennine range and the Westmorland

border from the Durham side; to visit the waterfalls of High Force and Caldron

Snout; and, if possible, to get as far as High Cup Nick and the junction of

Crookburn Beck and the Tees (where meet the counties of Cumberland, Durham and

Westmorland). As we had no car and no bus guide, we were uncertain to what

extent we might be able to carry out this programme. In the end we were able not

only to complete the whole of it but even to add to it, owing to the kindness of friends

in the hotel who gave us a lift in their car. Once again I render thanks to

motorists, and if ever Mr. and Mrs. Harris should read this book I hope they

will realise how grateful my wife and I are to them. I hope they will also bear

witness that we did not throw out hints or fish for a lift, or hang about in the

front hall of the hotel in a hopeful, expectant manner. "Sursum Corda" - Lift up

your hearts - is the motto of my old school, but "Lift up your friends" seems to

be the text followed by the Harrises, for I know now, since I learnt later, that

they make it a rule never to go out for a drive without first offering a lift to

somebody.

In this way, and with them, we planned overnight a combined operation by car and

on foot to High Cup Nick. It would have to depend on the state of the weather

but we would get to Caldron Snout anyhow.

We woke to find pouring rain and a high wind from the north-west. We stowed our

spare shoes and stockings in the car and set off from Heather Brae Hotel, where

we were staying, along the road to High Force. We had seen the wonders of this

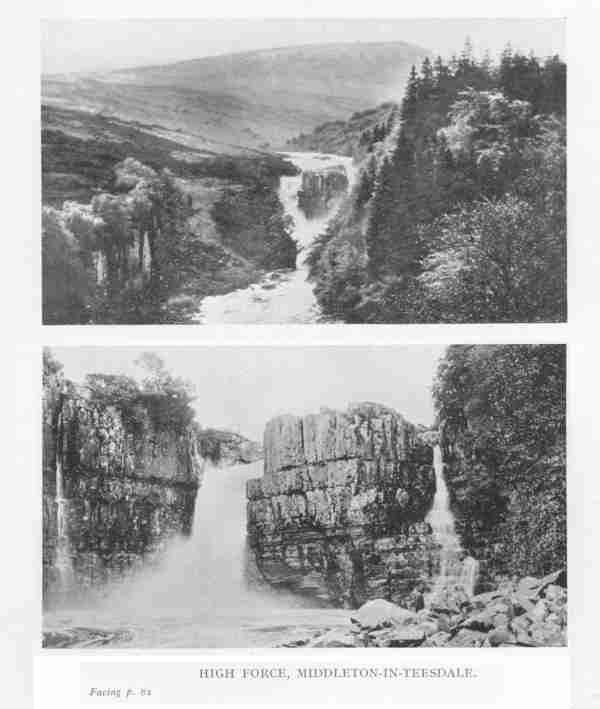

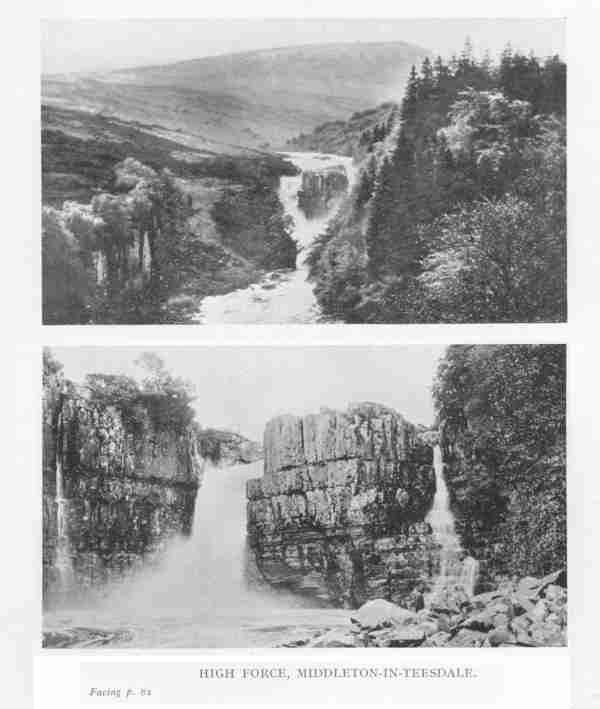

place on the previous afternoon. High Force has been described as "the finest

waterfall in the kingdom" with which I entirely agree, for though I have seen

many forces and falls in different parts of Westmorland and Cumberland and other

counties, I have certainly not seen anywhere else such grandeur of setting or

such a fine fall of water. You approach it from the high road down a path

through a wood of fir trees, and at the end of the path you hear straight ahead

of you the thunder of the fall. The Tees, at this point on its journey to the

sea, having carved itself a deep bed in the basalt, hurls itself over a

square-headed mass of rock with a drop of over 70 feet into the canyon below.

The colour of the water is brown from the peat bogs above the fall; the upper

part of the rock is basalt, with vertical lines of limestone beneath. In a

chapter called "Geology in Westmorland," in Kelly's Directory of the County,

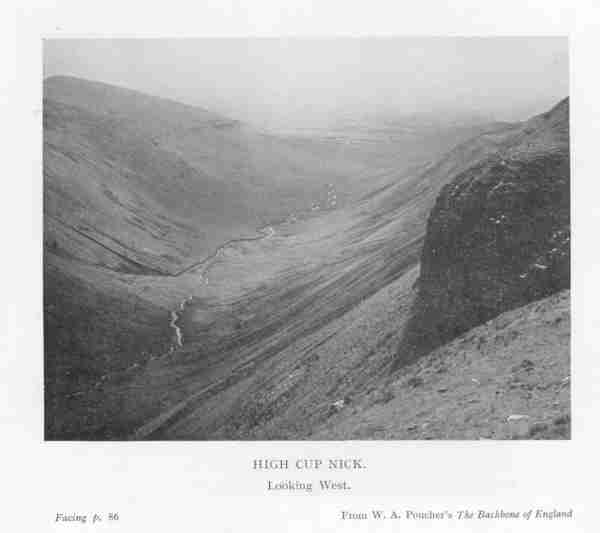

The ground is literally cut from under your feet. There is no foreground to look

at but you see, through the broad open gap at the western end of the horseshoe,

the Valley of the Eden some five miles away to the west, and beyond that in the

far distance the outline of the high fells of Cumberland in the Skiddaw

direction. It was like standing on the rim of an empty cup, looking across the

tea-leaves with a broken gap in the far side of the cup. The rim is in fact

composed of the same igneous rock that we noticed at High Force. "Here," says

the writer on that subject, "the Whin Sill is well seen along the western face

of the Pennine escarpment, one of the finest sections being at High Cup Nick,

where the basalt is 73 feet thick and has baked or altered the shale beds both

above and below it."

It is always a pleasure to visit a district with a geological formation and

flora and fauna different from those to which one is accustomed. This was

certainly true in our case, coming from London, and the Teesdale country, round

Middleton and up to High Cup Nick, had been no exception. In boggy, heathery

moorland on this higher ground one does not look for flora but the bird-watchers

had had a good day with the dunlin nesting and the large number of golden

plover, and now it was the turn for geology. Nothing like the precipitous basalt

edge of High Cup Nick had been seen before by any of us.

[text omission]

[88]

when we explained to him which way we had been to High Cup Nick that by the time

we got back to Cow Green we should have walked 15 miles as near as made no

matter. He seemed to imply, without actually saying it, that this was not a bad

performance for us old 'uns, considering the weather and the rough ground, and

we old 'uns secretly felt rather pleased with ourselves. Mr. Airey thinks

nothing himself of walking the ten miles or so from Birkdale over the moor to

Appleby when he wants to go there to see his relatives, but his sister, being

unable to make so long and arduous a journey, walks a shorter distance, in the

opposite direction, to Langdon Beck where she can get a bus to Barnard Castle;

there she changes into another bus for Kirkby Stephen, and so to Appleby - a

journey of some 40 miles which take her 11 hours! On one very rare and memorable

occasion in the 1945 General Election, she and her brother were offered a lift

by car all the way from Cow Green, round by Middleton and Brough to the polling

booth in Long Marton which is about a mile from Dufton village. It was to be a

long drive and a great event, but alas! it never came off. The Aireys arrived at

the appointed time and place near the Tees where the car was to meet them, but

when they got there the road was bare; there was no car and so their votes were

never registered.

* See p. 21.

Elections are favourite topics of conversation with farmers, quite apart from

the political issues involved or the party programmes. Indeed a far greater

interest is taken in the character of the candidate than in the cause for which

he stands. If the modern candidates of to-day are blameless, worthy men, then

let us go back to some ancient Victorian day when the hustings really were

hustings. "Do you remember old Mr. X?" asks a farmer friend of mine. How could

I, seeing that he was dead before I was born, but I had heard tell of him so I

say "Yes," in the hope that my friend will continue. "He was a great Parliament

man," he went on, "but he had his failings." My friend then looked at me in a

very knowing way and raised his elbow twice, fearing perhaps that I might have

overlooked his first movement.

He pursed his lips outward and drew in a quantity of breath in a disapproving

way and added "Ay, he went bit mark." I missed the point of this and then saw

it. He, the parliamentary candidate had overstepped the mark; he had gone past

the mark; he had gone by the mark. "He went bi' t' mark" my friend repeated.

Then followed a story of how this same candidate on one occasion was to have

addressed a public meeting in a Town Hall; and all the people came; the place

was packed ; they waited and waited; but the candidate never arrived; "and then

word coom that he'd got the tuithache." More knowing winks from my friend.

Of another Conservative M.P. at a later date it was said by Liberal critics that

the man wasn't a suitable member for Westmorland at all, seeing that he seldom

went to the House and never spoke during the whole session. To which came the

famous, oft quoted Tory reply: "Better if he stayed in his hotel aw' t' time

than bin a Liberil." A delightful idea this, that the representatives of the

people who were returned to Westminster were constrained to dwell in hotels! It

might be true of 1947, housing accommodation being what it is, but very unlikely

in the eighteen eighties when practically every M.P., whether a Liberal or a

Conservative, had or took a house in London while Parliament was in session.

That two lonely farms at Birkdale situated in a wild mountainous district,

separated from their polling station by miles of moorland should be included in

Westmorland at all seems to a mere visitor at any rate to be a clear case for an

alteration of the county boundary, because Birkdale is for all practical

purposes in Teesdale. It is to Middleton-in-Teesdale that the farmers come on

Saturdays for groceries and gossip, and though the two farms are in Dufton

parish there is no possibility of their using Dufton for either social or

religious purposes, separated from it as they are by miles of heather, bog,

becks and the high watershed.

To alter the boundary, however, and bring these farms into Durham would, I

realise perfectly, lead to a fierce controversy into which I would not dream of

entering. It so happened that while we were there, a proposal had been made

under a County Boundary Commisson to make some adjustments in another part of

Yorkshire. A local paper had flared up at once. "North Riding will fight" was

the heading, and underneath I read "full resources will be used against any

unreasonable attempts to annex any part of the Riding." There was the spirit of

the Lady Anne Clifford alive again!

CROOKBURN BECK

Westmorland is, to a small extent, a coastal county bounded by the sea at the

head of Morecambe Bay and by four continguous counties, namely, Lancashire,

Cumberland, Durham and Yorkshire. It therefore follows that there are four

three-shire meting places. There are firstly the three shire stone at Wrynose

above Little Langdale (probably the best known and the most frequently visited

of the four); secondly, the county stone on Crag Hill near Kirkby Lonsdale;

thirdly, the junction of the Tees and Maize Beck at Caldron Snout; and fourthly

the junction of the Tees and Crookburn Beck in the extreme north-east corner of

Westmorland.

It is the last of these with which I now deal, and I suggest that it might be

called the Crookburn meeting to distinguish it from the others. As our

headquarters were then at Middleton-in-Teesdale we approached it from the Durham

side, but you could get to it just as well if not better from Alston in

Cumberland. The distance from Middleton to Alston by the main road is about 22

miles; 14 from Middlton to the top of the pass and thence a run of eight miles

downhill into Alston. It is at the top of the pass that the road crosses over

the little (as it then is) Crookburn Beck, and it is there that you have to

leave the car and start walking. If you (or your friends who may be kind enough

to lift you) can spare the time and the petrol for the longer journey, it is

well worth while to drive the whole way to Alston and back, because by going

over the pass and returning up the hill you get a better picture of how

Westmorland and

Cumberland meet at this point and how Crossfell on the northern side dominates

their meeting. We were fortunate in being taken the long way.

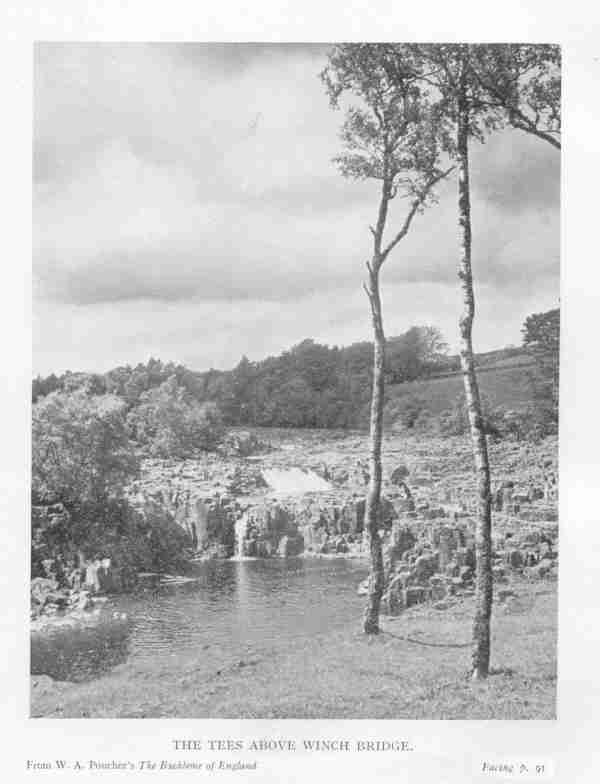

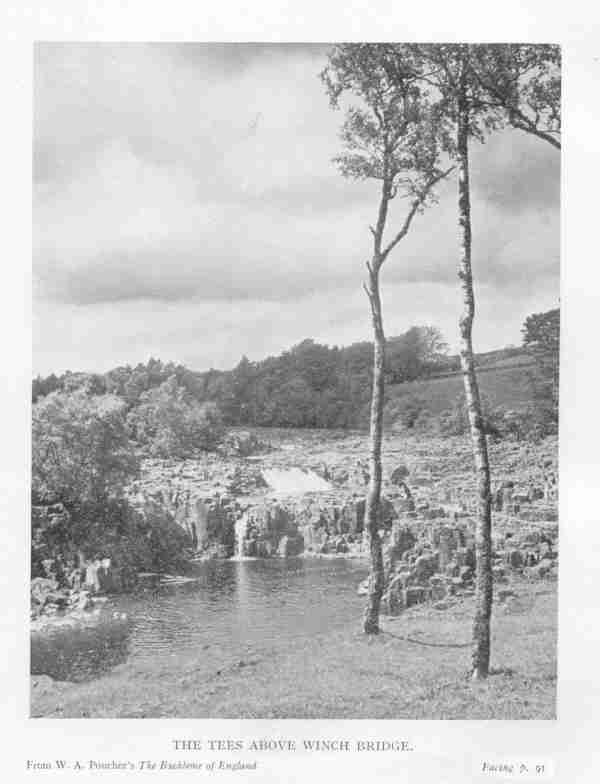

But first we were to see a very lovely bit of the Tees a few miles to the north

of Middleton and to the south of High Force. We left the car and walked across a

field to Scorberry Bridge; here we crossed over the Tees to the Yorkshire side

where we noticed a wealth of wild flowers; one field, in particular, covered

with pale orchis, another with wild pansies of varying colours and sizes -

purple, yellow, blue and yellow half and half, and pure white. We then walked

upstream to Winch Bridge where we recrossed the river to the Durham side and so

back by a footpath to Bow Lees and the car.

As we had already seen High Force and Caldron Snout and Langdon Beck, we passed

these by, and went steadily forward up the main road to Alston with the Harwood

Beck below us on our left. We had also passed by a number of quarries from which

great quantities of road material are being taken, after being put through high

and hideous mincing machines. Formerly, and until recently the London Lead Co.

owned and operated lead mines here. The Company was formed in 1692 under a

charter of William and Mary, and finally closed in 1905 after 200 years of

activity. The principal lead mines were in this part of Teesdale, but owing to

the low price of the metal and the decreasing percentage of silver found in it

the Company came to an end.

An industry that still survives in this neighbourhood is that connected with

barytes or sulphate of barium. This is a heavy, white mineral occurring in

veins, carrying lead and zinc ores. It is used in the preparation of white

paints for wallpapers and for bleaching flannel. Westmorland has been an active

producer of barytes at Brough and at Dufton Fell, and there is a mine that we

saw working at Cow Green close to the Tees above Caldron Snout.

It is a long pull up the Alston road to the top of the pass. Here at Crookburn

Bridge (see ordnance map) you take an old, disused road called Yad Moss Lane,

which after about a mile or more becomes a sort of grass terrace walk with a

magnificent view across to the west. Below is the junction of Crookburn Beck and

the Tees, where the three counties (Durham, Westmorland and Cumberland) meet;

beyond is the towering height of Crossfell in Cumberland, just over the

boundary. It is one of those places which in the days of my childhood used to be

called "scream points." They were given this name because, when you came to

them, you couldn't help calling-out "Oh!" The earliest "scream point" that I can

remember was on the road from Kendal to Staveley, where, as you come round a

corner, you suddenly see the whole range of the high fells of the Lake District

spread out in front of you. No visitor can go there on a fine day without

exclaiming vociferously: "Oh, how lovely!" ; in short, he "screams" when he

reaches that "point." If he doesn't there must be something amiss with him. This

spot on which we now stood near Crookburn Beck is a real "scream point."

From this grass terrace you can either follow the old Yad Moss Lane, which

becomes Peghorn Lane, downhill to Langdon Beck Hotel, or, if you have left your

car or bicycle at the top of the pass you can return, as we did, to Crookburn

Bridge on the main road. I am well aware that the traveller who comes back from

a far country with stories about places which he has seen that others have never

seen is liable to become, if not discredited at any rate regarded as a noted

bore, with no one to check the truth or stop the flow of his yarsn, but I have

met so few people in Westmorland who have ever seen the junction of the

Crookburn Beck and the river Tees that I merely recommend those who are fond of

scenery to go there at the earliest possible occasion, and I leave it at that.

1 * Kelly's "Directory of Westmorland," 1938. p.13.

2 "The Handbook of British Birds," H.F. Witherby, 1940.

3 W.A. Poucher, "The Backbone of England." Country Life, p.

194.

Thanks to Diane Coppard in Leicestershire for transcribing this! Reproduced by

permission of Tim Clement-Jones.