Page last updated 31/05/07

A Tour In Westmorland by Sir Clement Jones, published 1948

CHAPTER X

KIRKBY LONSDALE

A BOUNDARY WALK

It was about the lovely close of a warm summer's day when we arrived at the Royal Hotel, Kirkby Lonsdale - so lovely in fact that it was quite impossible to sit indoors after dinner. And what can be more agreeable than to potter about on a fine evening in a small and beautiful town such as this? Kirkby Lonsdale has been praised by Ruskin and painted by Turner. A score of artists, antiquarians, poets, historians and photographers have all tried their hands at it; I need hardly say there is a picture of the Old Bridge in this (1947) year's Academy. Nor need there be the least surprise at this worship, for it is a place of unusual charm.

We were taking that form of holiday that has been called "going abroad in England." I like it very much, and in these days when a round of country house visits has become but a memory of the past, owing to the breaking-up of estates, the shutting-up of bedrooms, and the shortage of those whom we no longer dare to refer to as "servants," I think a taste for seeing certain sections of England bit by bit, avoiding large cities and putting-up in comfortable inns (of which there are many), is one that might be developed with advantage.

"It is not only when we cross the seas," wrote Stevenson, "that we go abroad; there are foreign parts of England."

1Having reached your destination, you sign your name in the hotel visitors' book, find your bedroom, unpack and then wander forth. Explore the place in the same way as you would a foreign town. Visit the church; the market place; the little side streets; the ruined castle on the hill; lean on the old bridge; take it quietly; do a little shopping; buy a few picture postcards; get a local newspaper. Do these things and you will find that there is much to be said for "going abroad in England."

The first morning that we were at Kirkby Lonsdale was warm and sunny, and after breakfast I sat on a seat outside the hotel in the Market Square, watching the moving picture; the postman on his rounds; the buses coming in and pulling out - just as the stage-coaches must have done 150 years earlier; farmers and their dogs in solemn communication; women with shopping-baskets working like bees in and out of the grocers' and chemists' hives; an old man in riding-breeches with a young girl in jodhpurs waiting for their horses; cars stopping for petrol at the pump; errand-boys (or are they errant-boys?) on bicycles.

Soon I was joined on the seat by an old man, who, on finding that I was not an "off-comer" but a native of his own county and that my home-town was only 13 miles away, at once became an old friend and told me, in his broad Westmorland dialect, a string of good stories of which I can here repeat two. I told him that my father had been a friend of a former Vicar of Kirkby Lonsdale, whom I named. At once the old man beside me became interested; had I ever heard tell of the story of this canon and his verger? "No," I said. "Well, it was this way. T' ould canon nawticed that t'congregations were falling-off; fawkes wasn't coomin' to t' church as they hed doon a while sen. Saw the canon says to t'verger" (and at this point my friend dropped the dialect and assumed what I can only describe as the stage curate's voice): "Tell me, verger, why do not the people come to hear me as they used to do? What is wrong? Would it be better, do you think, if I were to put more fire into my sermons?" (Then reverting to the dialect). "Nay," said t' verger, "I dawn't knaw. Ther's soom fawkes think it ud be better if yer put more of t' sermons into t' fire."

Having let the laughter (his own and mine) that followed this story fade away, he was almost immediately reminded, either by the sight of two farmers in front of us in the Square or more likely by nothing at all but a desire to continue talking, of another tale. "There were two farmers," he began, "drinking gin in the Green Dragon yonder." I looked to the left and saw the pub indicated. "One of them was boasting about getting his three daughters married. Each of them was to have £3,000 on her wedding day. All the young men would want to marry them." "Nay," says t' oother farmer, "you'll never git your daughters wed without you raffle 'em, and I'll see as none of my lads take a ticket!"

Pleasant as it was to sit in this idle fashion in the market place, there was a great deal more sight-seeing to be done. First of all there was the church. In Nicolson & Burn's "History"

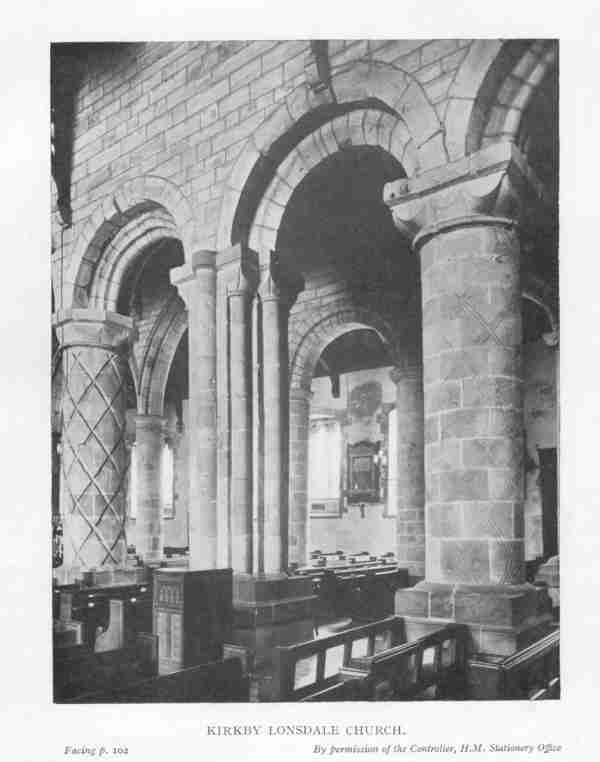

2 there is a complete definition of the name: "Kirkby Lonsdale, that is the kirk-town of Lonsdale, hath its name from the dale in which it is situate, through which the river Lon (corruptly called Lune) runs all along from north to south. The parish is bounded on the east by the county of York and on the south by the county of Lancaster." Formerly the parish was ten miles in length, cross-wise from four to six, and contained no less than nine townships including Casterton, Barbon, Middleton and Firbank. The Church of Kirkby Lonsdale is dedicated to St. Mary and belonged, before the Reformation, to the Abbey of St. Mary's, York. After the Dissolution of that abbey, the patronage of the vicarage was granted to Trinity College, Cambridge, by Queen Mary in the first year of her reign. The advowson and patronage of Kendal and Heversham in the same county were also given to the same college at the same time.As you enter the church by the south door you see straight ahead of you three massive, magnificent Norman arches on the north side of the nave. These are rightly regarded as the chief glory of this beautiful church. They were built soon after the Conquest, about the year 1100, and in their style and decoration they resemble those in Durham Cathedral and Waltham Abbey. Their size and their unfinished character seem to show that they were intended to form part of a projected but unbuilt church, for the pillars on the south side of the nave re of a later date, probably about the latter half of the 12th century, and are less elaborate; the remaining arches of both arcades are Early English and with the chancel date from about 1200. The southern and western doorways and the lower part of the tower are Norman work, but the rest of the tower was rebuilt in 1704. The outer north aisle was added in the reign of Elizabeth.

There is so much to see both inside and outside the church

that plenty of time must be allowed for a visit. We went there on three

successive days, and even so we should have liked to stay longer. An old friend

of mine, J.W. Clark, who was Registrary of Cambridge

University many years ago, known affectionately as "J" to vast numbers of

undergraduates, told me once that he was asked for advice by a man who was going

to Athens for three days and wanted to know what he should see. "The first day,"

said "J," "you will, of course, go to the Parthenon; the second day you will go

again to the Parthenon; the third day you will go once more to the Parthenon." I

feel much the same in giving advice about Kirkby Lonsdale and its church.

There is, however, in this lovely church one sad feature - one serious blot - in the north-east corner. Here is to be seen all that is left of the Middleton Chapel, founded in 1486 by William Middleton. There was formerly in this chapel a beautiful alabaster monument representing a knight in armour lying on his back with his resting on a helmet and by his side his wife. But alas! to-day there is little left of its former beauty. In the 18th century this north-east end of the church was reconstructed and reduced in size,

3 so that only a mutilated portion of the tomb remains; the man's head is on his helmet, but his legs are missing. Was there ever a sadder case of procrustean truncation? For here, but for the cutting down of the size of the chapel, and the cutting off of part of the effigy, might have been a perfect monument such as the tomb of Thomas, Lord Wharton, and his two wives in Kirkby Stephen Church (1568); or the black marble and alabaster altar-tomb of Margaret (Russell), Countess of Cumberland, erected by her daughter Anne in 1616 in Appleby.

The Middletons of Middleton Hall were a powerful family in

Westmorland from the reign of Edward III until that of Charles I. They owned the

manor of Middleton in the parish of Kirkby Lonsdale, between the Valley of the

Lune and the eastern boundary of the county, bordering on Yorkshire. Their sons

and daughters married into what in Anthony Trollope's time used to be called the

"governing" classes; they made matches (as did the Greshams of

Greshambury in Barsetshire) among the neighbouring landowners:

Musgrave of Hartley Castle, Ducket of Grayrigg,

Bellingham of Burneshead, Fleming of Rydal, Tunstall of Thurland Castle, Lowther

of Lowther, Bindloss of Borwick - these were some of the North Country families

with which they formed alliances.

It was then, in the reign of Charles I, that the state of affairs at Middleton Hall began to decline. There was anciently a chapel in it, but that went into decay; the deer in the park were destroyed about the year 1640; the family, as we have seen, were great sufferers in the civil war; the tenants purchased the freehold of their farms at different times; in 1644 the male line of the family ended, the inheritance descended through daughters and, though part of the demesne remained in the female line, the estate was broken up.

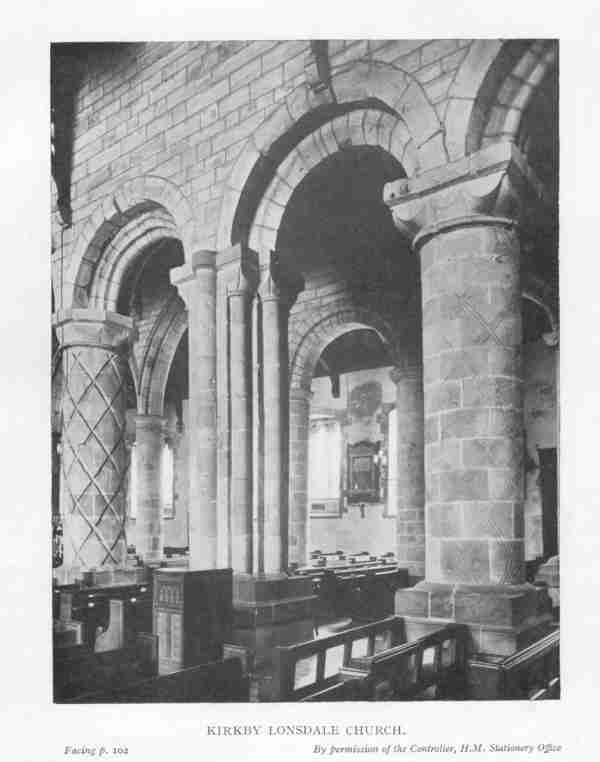

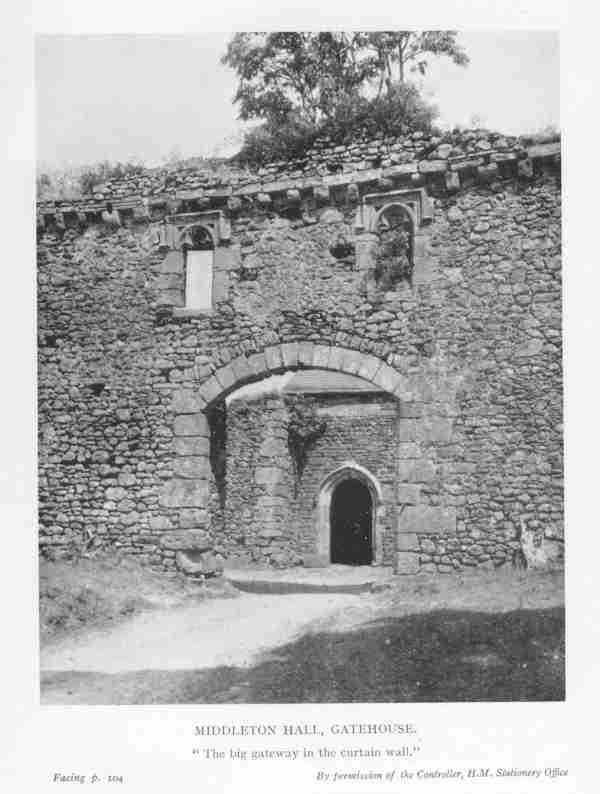

Middleton Hall is an old castle-like building - domus defensabilis - and is now only used as a farmhouse. But it retains a great deal of its old dignity and has been described

5 as "our best local example of the domestic architecture of the 15th century." Consisting of a central block, with transverse wings at either end, it is surrounded by a massive wall forming an inner and outer courtyard. "Traces of the barmkyn or walled courtyard," writes W.T. McIntire, "into which flocks and herds could be driven for safety, when the beacon flare gave warning of the approach of raiders, are still to be seen at Burneside Hall, Middleton Hall, Wharton Hall and elsewhere."We had visited Middleton on a previous occasion in 1946. It was a cold day and we were grateful to Mrs. Todd, the tenant'' wife, for showing us into and round this interesting house. We were still more grateful to her for saying that we could eat our sandwiches in the kitchen by the fire, and when she saw what meagre fare we had brought she boiled us each an egg and made some tea. Kindness itself. From the courtyard the entrance to the house is through a wide, pointed doorway; inside are the screens or passage; on the left of the passage are three other pointed doorways leading to what had been in former days the kitchen, the buttery and the cellar; on the right of the passage is the hall. (This arrangement of entrance through screens is similar to that existing in many college dining-halls, for example, the entrance to the hall of Trinity, Cambridge, from the Great Court).

The hall entrance has a substantial oak door, panelled and studded with iron; the hall itself is 28 feet by 24; it is lighted by four early perpendicular windows; it has a blocked, arched fireplace next the passage screens. At the opposite end of the hall, where stood the dais, are two doorways, one leading to the withdrawing-room lined with oak-panelling and used on Sundays as a Methodist Chapel - a collateral descendant perhaps of the ancient chapel that fell into decay. On the floor above is a bedroom with a mantelpiece displaying the arms of the Middleton and Tunstall families.

You leave Middleton Hall by the big gateway in the curtain wall and, as you walk down the long, straight drive that leads to the high road, you cannot help feeling, as you feel on leaving Wharton Hall and so many other old fortified farmhouses in Westmorland, a little sad that so much of the former strength and beauty of the place has passed away.

To return to Kirkby Lonsdale Church, it may well be that the Middleton chapel in the north-east corner was reduced and altered for the worse in the 18th century because there were then no Middletons at the Hall to ride over to Kirkby and prevent the family tomb being mutilated.

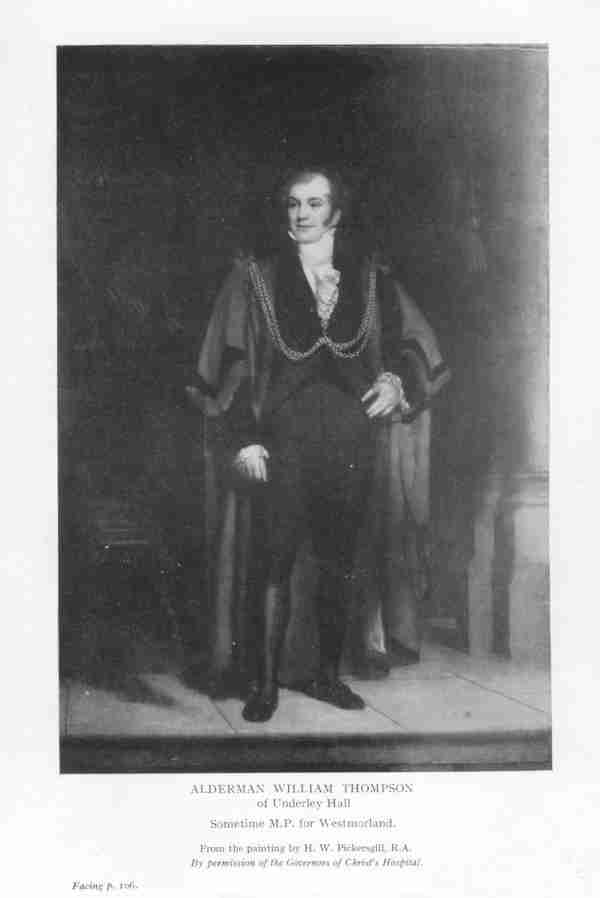

Leading from the churchyard at Kirkby Lonsdale in the direction of Underley there is a terrace walk, perched high up above the rive Lune, from which you can get (as we got on that lovely June evening when we arrived) a magnificent view of the surrounding fells - Barbon and Casterton and Leck. Underley Hall is about a mile from the town. It was built in 1825 by Alexander Nowell, who sold it to Alderman Thompson, a member of an old Westmorland family long settled in Grayrigg parish, who became Lord Mayor of London and was at one time M.P. for Westmorland. It has been described as "a fine mansion in the Tudor style considerably embellished in 1867 and enlarged in 1873 by the addition of a tower, etc.; the park is well-timbered and bounded by the river Lune." It would be difficult to improve on that description of the place, unless it were to say that the embellishments and enlargements were due to the wealth amassed by Alderman Thompson whose daughter Amelia married in 1842 the then Lord Bective. Their son, Lord Bective (1844-1893), lived at Underley and was M.P. for Westmorland for several years. As a younger man, when he was Lord Kenlis, he lived in great style to the delight of the people in the neighbourhood; the splendours of his shooting-parties, setting out from Underley in a coach and four, are spoken of even to this day; his carriages are still remembered. I have talked to two people - one an old lady over 80, the other a retired postman (who told me he was born in 1864) both of whom said they could remember as children seeing Lord Kenlis driving through Kirkby sitting back in his carriage drawn by four horses, with postilions in white buckskin breeches. This must have been about the year 1870. To-day Underley is a girls' school, and one wonders whether in their Latin exercises the young people ponder over the old tag "sic transit gloria mundi."

It was our intention when we came to Kirkby Lonsdale to walk to the County Stone, where meet the three counties of Westmorland, Lancashire and Yorkshire. That was our objective and, being uncertain about the best way to approach it, I wrote to a man with whom I had been at school at Haileybury many years ago - Major Gibson of Barbon. He very kindly gave me exact details of how to get there, which I will here set down, as they would be useful to anyone anxious to take that particular walk and get the view form the County Stone. "I should suggest motoring from Kirkby at least as far as Bank House, Leck, where the keeper for Low Leck Fell lives; then walking up a roughish road, degenerating into a track; after about two and a half mils you pass just above High Leck Fell House; after another half mile the track disappears and for the next one and a half miles you have to walk over very rough ground partly covered with heather. The County Stone is where the walls meet."

In the end we reached our objective, the County Stone, but by a totally different route and for the following reason. At breakfast in the hotel we had the good fortune to be placed at the same table as one of those really helpful people who offer to give lifts to walkers on the dull road-slogging part of their walks. She and her two small daughters were going that morning to Barbon; could she give us a lift that far on our way to the County Stone? I do think that motorists who are thoughtful of walkers deserve some special reward - free transport in the next world perhaps - for what they have given in this, and I know how grateful we were to Mrs. Bowring in giving us that lift. She drove us by way of Casterton and Whelprigg to the back gate of Barbon Manor. There we took to the road and walked up Barbondale as far as Blindbeck Bridge. Turning right-handed at that point, we took the old disused road to Bull Pot (where the shepherd and his dog Hemp did such gallant rescue work in the blizzard

6 ). Here we turned left and up the fell where the old road, previously used no doubt for carting coal, soon degenerates into a mere track. The ordnance map still marks "Old Coal Pits" just above Bull Pot.There must have been a considerable amount of coal extracted in this neighbourhood at the end of the 18th century because in the Addenda to West's "Guide"

7 the author refers to this particular traffic on the roads near Kirkby Lonsdale: "The number of small carts laden with coals, and each dragged by one sorry horse, that we met, was surprising to a stranger. Many of the smaller farmers betwixt Kirkby Lonsdale and Kendal earn their bread with carrying coals during most parts of the year, from the pits at Ingleton, Black Burton, or properly Burton-in-Lonsdale, to Kendal and the neighbouring places for fuel and for burning lime in order to manure their land. These beds of coal we were informed, are six or seven feet in thickness."Beyond Bull Pot the walk became, for a time, less interesting, for the clouds came down and we could only see a short distance ahead of us. We skirted round the should of Crag Hill towards Ease Gill and there had lunch. Luckily the weather improved, the clouds lifted, and we walked on and up to the County Stone where the walls meet. We were rewarded by a really good view from the top; we looked across to Whernside and Ingleborough, and down to Deepdale and Dentdale below; while in the far distance, to the south-west, the sun was shining on the Lune and on the sea beyond Arnside.

There was very little of interest in the flora on that particular fell, just bog-cotton and bilberry plants and tufts of coarse grass; no flowers or ferns until quite low down in Ease Gill which here forms the boundary between Westmorland and Lancashire. The birds that we noticed on that occasion were peregrine, curlew, pippits, larks and wheatears.

As we turned to come down, low clouds and rain again descended on us, so that being unable to see ahead, and not knowing the nature of the ground we thought it best to keep close to Ease Gill and follow that. We walked along the steep side of the Gill - not at all comfortable, on account of the bad-going through heather and bracken - as near the beck as possible, keeping it sometimes in sight, in breaks in the cloud, and always in sound. "Loud was the Vale" as the water tumbled down the rocks beneath us. And then suddenly, as we scrambled along the Gill, a most uncanny thing happened. There was no more noise of rushing water. It had completely ceased. Where was the beck? A lift of the cloud showed us a dry river-bed below us and ahead of us with no water in it. The beck had in fact gone into deep pot-hole in the limestone, leaving its former course a dry bed of boulders.

No one had told us of this strange happening, but when we got back to the hotel we found that "Everyone," so to speak, knew all about the disappearing underground stream; even the "Boots" said "There were always a lot of pot-holers coming over from some college to see it."

In West's "Guide," published in 1799, there is an account of a similar place in the neighbourhood: "It is a round steep hole in the limestone rock, about eight or ten yards in diameter and of a tremendous depth. We stood for some time on its margin in silent astonishment not thinking it safe to venture near to its brim. The profundity seemed vast and terrible. We plumbed it to the depth of 165 feet, 43 of which were in water. A subterranean rivulet descends into this terrible hiatus which caused such a dreadful gloom from the spray it raised up, as to make us shrink back with horror. The waters run form its bottom above a mile underground and then appear again in the open-air. After having excited the several passions of curiosity, dread and horror, we went a little higher up the mountain."

Mr. John Hamer, writing with less emotion but more authority in an excellent booklet on the caves of Ingleton,

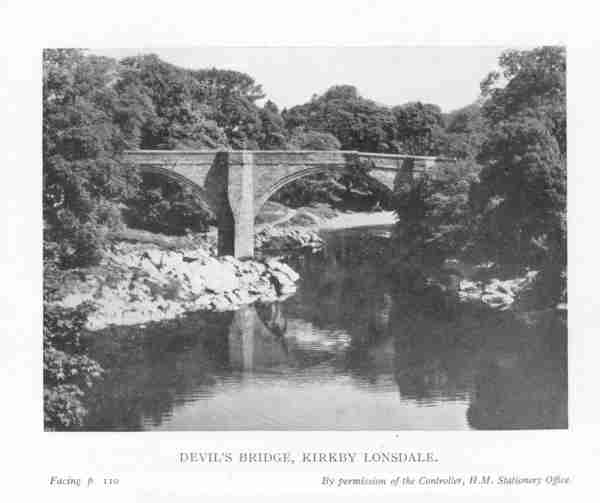

8 describes the exact walk which we took and I therefore do not think I can do better than quote what he says: "Further caves and pot-holes are reached by descending the valley down which Ease Gill Beck flows. Progress is made difficult by a tangle of bracken and heather and care should be exercised on approaching the ravine as its rocky sides, crowned with trees and foliage, are over 100 feel in depth. Ease Gill Kirk, as this limestone gorge is called, was once a massive cavern, the roof of which has collapsed leaving an open valley of great grandeur. The beck, the Ease Gill, has deserted its former bed and now reappears below the gorge." We returned to Kirkby Lonsdale by striking across the lower slopes of Casterton Fell making right-handed for Bindloss Farm and so under the railway, across the high road and over the Devil's Bridge.This bridge over the Lune is among the monuments specially mentioned in the Royal Commission's Survey.

9 It is carried upon three-ribbed arches of singular beauty, the centre arch rising 12 yards above the ordinary height of the river. Its date is uncertain. In Bulmer's "Directory of Westmorland" (1885) we read: "By some it is supposed to be of Roman origin whilst others think it the work of Norman hands." But the Royal Commission of 1936 gives no support to any such views and proceeds more cautiously: "There is record of a grant of pontage for the repair of the bridge in 1365 but the round form of the arches would seem to indicate that the existing structure was rebuilt not earlier than late in the 15th or early in the 16th century."

I was asked why it is called the Devil's Bridge. The only answer I know is the one that is contained in the local story of the Old Lady who wanted to cross the Lune but was unable to do so because there was no ford at that spot. Whereupon, of course, Old Nick appeared and offered to build a bridge, on condition that the first living creature that passed over should be his for ever, having evil designs on the Old Lady's husband. The Old Lady assented and in the morning sure enough there stood the bridge. Taking with her a bun and her little dog, she went to the ridge and threw the bun across it. The dog ran after it and was the first living creature to cross. The Devil thus outwitted uttered a howl and disappeared.

1 "Memories and Portraits," by R.L. Stevenson.

2 Vol. I, p. 243.

3 See plan on p. 134 of "Historical Monuments"

4 For a detailed account of the Middletons, their family, their marriages, their property, see Nicolson & Burn, Vol. I, pp. 252-8.

5 "Historic Farmhouses of Westmorland," published by Westmorland Gazette Ltd., 1944, p. 88

6 See Chapter 2

7 Mr. West died 10th July, 1779, "at the ancient seat of the Stricklands at Sizergh in Westmorland."

8 "Dalesman Pocket Books" - 2; "The Falls and Caves of Ingleton," 1946.

9 See p. 136 of the Survey.

Thanks to Diane Coppard in Leicestershire for transcribing this! Reproduced by permission of Tim Clement-Jones.