Page last updated 28/01/04

A Tour In Westmorland by Sir Clement Jones, published 1948

CHAPTER VII

APPLEBY

LONG MARTON - CROSBY GARRETT - SOULBY - A

SECOND VISIT TO MALLERSTANG - A DRIVE OVER STAINMORE TO MIDDLETON-IN-TEESDALE

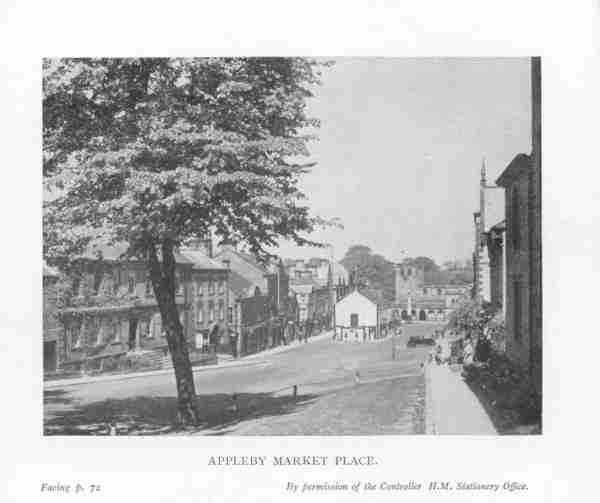

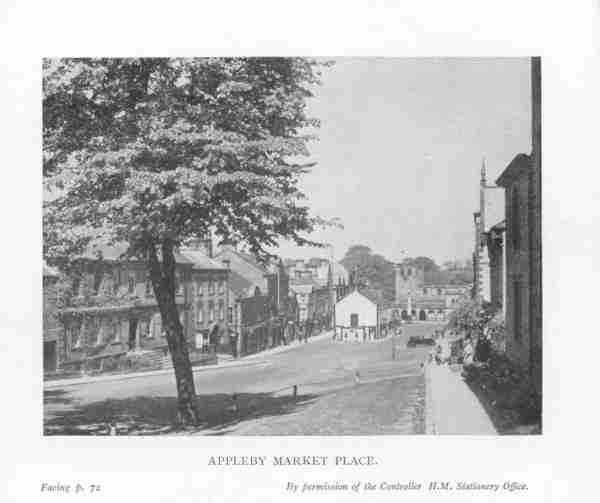

For our third and last day in the Bottom of Westmorland we had

chosen Appleby, London Marton, Crosby Garrett and Soulby in that order. We

therefore drove straight from Kirkby Stephen to Appleby (ten miles), and, after

crossing the bridge over the Eden, left the car in the market place at the foot

of the main street called Boroughgate.

Appleby, the capital of Westmorland, has always been a place

of importance. In 1179 it was put on a level with the city of York by Henry II,

who bestowed on it equal privileges; York received its charter in the morning

and Appleby in the afternoon of the same day. Appleby is a municipal borough and

an assize town, and from the reign of Edward I (1295) until the Reform Act

(1832) it was a parliamentary borough returning two members to Parliament.

William Pitt, sometime Prime Minister, was M.P. for Appleby, 1781-6. Few English

towns can have suffered more from "battle, murder and sudden death" than

Appleby. In 1176 it was burnt by William the Lion, King of Scotland; hardly had

it recovered from this calamity when it was again devastated by the Scots in

1388, when it was "totally burnt and wasted by those cruel invaders"; in 1598 it

suffered severely from the plague; during the civil war it was fortified by Anne

Clifford for the King and was held by the Royalists until the battle of Marston

Moor in 1644, when the castle and

town were surrendered to the Parliamentarians.

APPLEBY

For a short description of Appleby it would be hard to beat

the one given in "The Beauties of England," published in 1757, to which I have

already referred: "The chief Beauty of the Town consists in one broad street

which runs with an easy ascent from North to South at the Head whereof is the

Castle almost surrounded by the River, and with Trenches where the River comes

not. At the lower end of the Town are the Church and a School. Here also is a

Hospital for a Governess and 12 other Widows, called the Mother and 12 sisters.

The Town stands on the Roman military way, which crosses the county from Rere-cross

on Stainmore in the East to the River Eden a little below Penrith in the West."

To amplify this account we can best begin with the Parish

Church of St. Lawrence. There are some remains of Norman work in the lower part

of the tower, but in consequence of ravages by the Scots, already mentioned, the

history of the church, like that of the town, is one of rebuilding and

restoration. In the 13th century much of the earlier fabric had to be replaced;

after the 1388 raid the repairs of the 15th century included rebuilding the

tower; and in 1654-5 Anne Clifford took the church in hand in her usual

effective way and " caus'd a great part of Appleby Church to be taken down and

caus'd a vault to be made in the north-east corner for her to be bury'd in."

It is this particular corner of the church that has the

greatest interest, for it contains the altar-tombs of both Anne and her mother,

Margaret, Countess of Cumberland; both of them died in Brougham Castle, the

mother in 1616, the daughter in 1676; both of them were buried here; the

mother's tomb is of black marble and alabaster, on top of which is her recumbent

effigy in alabaster. She is dressed in a long cloak which covers her to the

feet, leaving only her face and her buttoned jacket visible; on her head is a

widow's hood and a metal coronet, and round her neck a small ruff. Anne's own

tomb which stands over the vault that she had "caus'd to be made," has no

effigy, but above it is a mural monument covered with a series of

shields-of-arms representing the descent of the house of Clifford.

From the church we walked up Boroughgate to St. Anne's

Hospital, the almshouse, founded in 1653 by Anne Clifford. The building has

great charm; it forms a quadrangle, containing thirteen separate dwellings and a

small chapel. On the west front there is the usual Lady Anne inscription telling

us that the Countess Dowager of Pembroke, Dorset and Montgomery had founded and

built these almshouses, and o the wall-faces in panels are set the usual

coats-of-arms, Clifford impaling Vipont, Clifford impaling Russell, Sackville

impaling Clifford, Herbert impaling Clifford. All very aristocratic and heraldic

and characteristic.

From there we went on to the castle gate at the top of th

hill. We had been looking forward to seeing the castle and it was therefore a

great disappointment to find, on asking at the lodge, that the whole place is

completely closed to visitors, owing to shortage of staff. Obviously te public

cannot be admitted to roam about in the castle without a guide, like sheep

without a shepherd. Some years ago I had (for a small consideration, I think)

bee shown the keep, know as Caesar's Tower, but on this occasion under no

consideration could we see over it, and we had to be content with looking at it

from a distance and reading about it afterwards.

Appleby is one of those castles, like Windsor or Warwick, of

which one can truthfully say "Once seen, never forgotten." Castles form so large

a part of the playtime of our early years whether on the sands at the seaside,

or in our "reading aloud" of Scott's novels, or by a rearrangement of chairs and

table in the nursery on great occasions and wet days, that the first sight of a

real, living and lived-in castle - not a mouldering ruin - pivots a great

thrill, and, even with advancing years, the visitor to an ancient castle can

renew this particular pleasure.

Appleby Castle is memorable chiefly, I think, by reason of its

position, perched high up on top of a cliff, with a sheer drop down to the river

Eden below. The most impressive part of the castle, as I remember it, and as can

be seen in the photographs, is the 12th century keep which stands

detached from the enclosing walls, and apart from the main part of the castle

towards the east. The castle suffered, as did the church and the rest of the

town, from the Scots and the civil war, and its history is one of destruction

and restoration. It was partly dismantled by the parliamentary army in 1648, but

the Lady Anne restored it in 1653. The existing house was largely rebuilt and

enlarged by Thomas, Earl of Thanet, with materials from Brougham and stones from

Brough in 1695.

We walked round the outside of the castle, came down the hill,

recrossed the Eden to the east side of the river and looked into St. Michael's

Church in Bongate. It occupies the site of the original Saxon church, and

contains a mixture of portions ancient and modern; the earliest surviving parts

of the building are 12th and 13th century. In 1659 the Lady Anne "caused Bongate

Church near Appleby to be pulled down and new-built at her charge," and, as

usual, she left her mark upon it; high up o the north wall is a carved cartouche

with the famous initials and date, "A.P. 1659."

In "Pennant's Tour (1773) from Downing to Alston Moor" there

is an engraving of Appleby Castle showing St. Michael's Church in the foreground

with a small belfry. The church must then have been very much as it was after

Lady Anne's repairs had been completed. The existing tower that we see to-day

was added considerably later, in 1886.

So ended our visit to another very lovely and interesting

place on the banks of the Eden. From Appleby we went on to

LONG MARTON

about three miles to the north. It is always called "Long" not

from its extraordinary length, for, as Dr. Burn says, "many other villages in

the Bottom of Westmorland are longer," but more likely to distinguish it from

some other place of a similar name and spelling such as Merton or Murton.

Spelling must have been much easier for people who lived in mediaeval times when

there were so many variations allowed.

The church is situated in the fields at a considerable

distance from the village, as we had also found at Dufton and Milburn, but it

may well be that these churches were purposely so placed in order to be equally

convenient for farmers and others in hamlets who lived at some distance from the

main village. To-day it is much less convenient for visitors, like ourselves,

who, finding the church door locked, had to go hunting from house to house in

Long Marton for the key.

On the south side of the church is a transept called "the

Knock porch," said to have been for the use of the inhabitants of Knock, a

village at the foot of Knock Pike about a mile north of Marton. Windows in the

church attest the ownership of the land here having been in the hands of those

families with whose names we have now become familiar, Clifford, Dacre,

Lancaster and Wharton.

The western tower, built of local sandstone, in three stages,

is Norman; so is the nave, and so it part of the chancel. It is a fine church

and well worth a visit, even if you do have a bit of a hunt for the door-key.

Next we came back on our tracks to Appleby and thence took the

Orton road south towards Asby. And here I must say a word about the wild flowers

that we saw by the roadside on this part of our tour. It was on this particular

afternoon (5th June) when we were driving along the road south from Appleby that

I made a not of them, though they were so remarkable both for their quantity and

beauty that I think I should have remembered them without any record.

Between two places marked on the map with the charmingly

abrupt names of Slosh and Hoff, we suddenly saw in the grass verge, which is

rather wide at this point, a mass of Primula farinosa. We pulled up instantly

and all got out to have a closer look.

In the western part of the county we have our own Primula

farinosa certainly, but in relatively small quantities and not, as you might say

in "bulk," as they are here beside the road. Indeed I know people who are very

careful how and to whom they reveal the exact whereabouts of this plant, and

quite likely will keep the information to themselves. If pressed they will

rather grudgingly admit: "Well, yes, I did see one or two up Long Sleddale"; or

near Kentmere or above Troutbeck, as the case may be, but without giving any

definite clue. But here there were not just one or two but whole sheets of them

- a primula counterpane covering the grass.

There were other flowers here, not uncommon ones but of great

beauty - the pale-spotted orchis and the slender butterwort rising from its

rosette of leaves, water avens, wild geranium or meadow crane's-bill, and what I

have always called by its Westmorland name of "shoes and stockings," which other

people tell me is more correctly known as yellow trefoil. May the ground of

heaven be carpeted with some such collection of wild flowers as those six -

especially farinosa and the spotted orchis - and may there be no hot-house

plants, no arum lilies or gloxinias!

CROSBY GARRETT

which is a village of great charm, tucked snugly in a deep valley at the foot of

Crosby Fell, about three miles from Kirkby Stephen. As you enter it, the first

thing you notice is the church standing in a commanding situation on top of a

steep hill or mount, considerably above the lower part of the village. It

dominates the position as, for example, does the church at Harrow. In the

eighteenth century this place was occasionally know as Crosby-on-the-Hill, but

Dr. Burn tells us that is was more usually called Crosby Garrett and that most

people at that time imagined that it got this name from the fact that the

highest rooms in houses are called garrets. But he adds that more probably the

word Garrett is a corruption of Gerard, from the name of the owner. There are

records showing that in the time of Edward I the place was always called Crosby

Gerard.

The manor and the advowson belonged afterwards for several generations to the

Soulby and Musgrave families who resided elsewhere, and there is not trace or

tradition as to where the manor house stood. Here, unlike so many other villages

in the Bottom of Westmorland, there is, surprisingly, no evidence of Clifford

ownership.

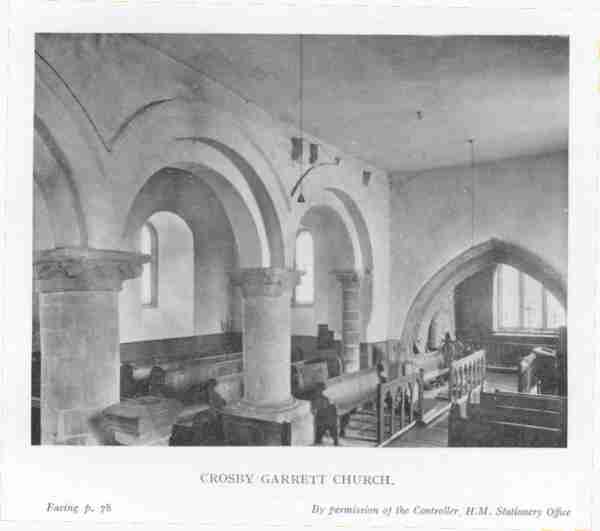

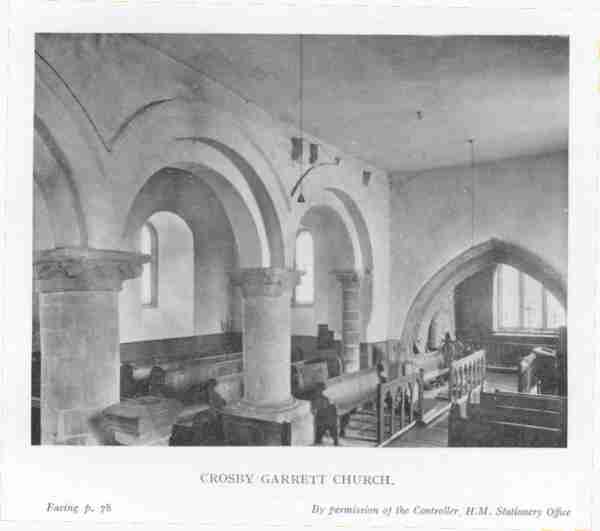

The church, which is dedicated to St. Andrew, contains some good Norman work;

the arches of the arcade, carried on massive circular pillars with carved

capitals are particularly fine; the early chancel arch is also interesting. It

is regrettable that in an otherwise beautiful old church the pews should be so

ugly. Perhaps, however, it is not entirely their fault since they were fashioned

(if such a word can be applied to them) about the year 1850 when taste in pitch

pine was pretty low; even in 1885 one visitor to the church wished the pews

could be changed, and he makes an excuse for them by saying "the seats are those

of about 30 years ago when ecclesiastical woodwork was not so well understood as

at present." He even went so far as to suggest making a change from deal to oak

which he says would be "very simple and of comparatively small cost." In 1947,

with seasoned timber almost unobtainable and the wages of carpenters what they

are, I can hardly imagine that any Parochi!

al Church Council would authorise removing the pitch-pine pews and putting oak

ones in their place, though I agree with the 1885 visitor that it would be a

very great improvement.

From Crosby Garrett we drove to the village of

SOULBY

about

two and a half miles north-west of Kirkby Stephen. Here again we are on Musgrave

land and not Anne Clifford's. It is in this parish that the Scandale Beck

(beside which we had been for a walk on the previous day near Ravenstonedale)

flows into the river Eden about half a mile from the village.

The church here was built in 1662 by Sir Philip Musgrave of Eden Hall. But,

apart from that, there is little for the antiquary to notice, and we were soon

on our way back to Kirkby Stephen.

As it was our last evening in this part of Westmorland, and as, owing to double

summer-time, daylight was no consideration, we decided that the place of all

others in that neighbourhood that called for a second visit was the Upper Eden

Valley under Mallerstang Edge which we had seen on the first day of our tour. So

we set forth again after tea by the Hawes road, through Nateby, passing

Lammerside on our right, and pulled up by the roadside close to the Eden where

she makes a bend round Birkett Common. From here we walked up the fell to the

east and, with every hundred feet climbed, we got a better and wider view to the

south; on our left the high outline of the Edge, with the patches of snow still

on its north side that we had noticed before; on our right the great flat-topped

mass of Wild Boar Fell; and in the valley between them the graceful musical Eden

swinging past us on her way to Kirkby Stephen, Warcop, Appleby and Cumberland.

After coming down from the fell, we watched various birds down by the river:

sandmartins; an oyster-catcher on nest; yellow wagtails and redshanks. This bit

of the Eden Valley was one of the best beauty spots - highlights if you like

that name better - of our whole tour, and I recommend those who are out for

fauna, flora and the view to drive south from Kirkby Stephen on a fine summer

evening ad take a walk up the fell in the direction of Mallerstang.

On the following morning the weather changed for the worse and we had a wet and

windy day for our drive over Stainmore to Middleton-in-Teesdale. Sadly we left

Kirkby Stephen, for it had proved a most convenient and comfortable headquarters

from which to explore the Bottom of Westmorland.

STAINMORE

And now we were going over to an entirely different country. Our road lay to the

north through Brough over Stainmore. That remote corner of the county, and the

road from Brough to Bowes was described about the end of the 17th century by Sir

Daniel Fleming of Rydal (1633-1701), a distinguished antiquary. He wrote:-

"From Brough the road leadeth over the ridge of fells. Here beginneth to rise

that high, hilly and solitary country, exposed to wind and rains, which, because

it is stony, is called in our native language Stane-moor; over which is a great

(but no good) road, the post passing twice every week betwixt Brough and Bowes,

and coaches going often that way, though with some difficulty and hazard of

overturning and breaking. All here round about is nothing but a wild desert."

Since that was written the road has been steadily improved, by turnpike and

tarmac, and is now very good. We were still "exposed to wind and rain," we were

surrounded by "a wild desert," but in the capable hands of my cousin, her car

was in no "hazard of overturning."

Stainmore is a great moor and watershed separating Westmorland from Yorkshire.

To the general tourist, racing past in a fast car, it is simply a stretch of

wild mountainous country and it is nothing more. But to the specialist or

hobbyist it is caviare of the finest flavour. It is full of interest for so many

different sorts of experts. It is like an old-fashioned Christmas bran-tub

containing a present for everybody; for the geologist, barytes and basalt and

other minerals; for the antiquarian, Roman remains; for the bird-watcher, hawks

and dunlin and duck; for the botanist, a wide range of plants and ferns; for the

entomologist, butterflies and dragonflies; for the painter, scenery; for the

sportsman, grouse.

Our road from Brough to Middleton soon parted from the Bowes road at the first

fork and we went to the left, up and up the long climb to the top of the ridge.

For some distance the road runs close to Swindale Beck, on its way down to

Brough. At the top of the watershed, about 1,500 feet up, we crossed the

boundary into Yorkshire. It was cold and wet; not much to be seen through the

rain; here a small tarn, there a lonely hut - "Dirty Pool" and "Old Rake," so we

read in the map.

Then began the long run downhill to the Tees, first passing, on our left, Lune

Head where rises another Lune (not the Lancaster one) on its way to join the

Tees and be emptied in the North Sea. On our right a reservoir filled by the

Lune and other becks; down and down we went, passing Wemmergill, famous for its

grouse moor and well-known in the eighteen nineties to readers of the

illustrated weeklies for its smart shooting-parties ("reading from left to

right") in beards, starched collars, deer-stalker caps and spats.

And so, after a few more miles of coasting downhill we reached the bottom,

crossed the river and entered Middleton-in-Teesdale.

This marked the end of the first stage of our journey, for it was here, at

Middleton, that our cousin had to leave us in order to attend a Diocesan

Conference. Before she left we went first to see the waterfall at High Force

which I describe in the next chapter, and then, as we waved goodbye, we all

agreed to meet again in the following year for another tour in the first week in

June, to see the rest of Westmorland that we had not seen and "do" those places

that we had left undone.

Thanks to Diane Coppard in Leicestershire for transcribing this! Reproduced by

permission of Tim Clement-Jones.